It’s unusual for a 44-year-old film to draw crowds into packed theatres during the peak of the Indian summer, but that’s exactly what happened when Umrao Jaan returned to the screens earlier this year.

The Bollywood classic, first released in 1981, is a period drama set in the 1840s, a time when British rule was taking form and a thriving court culture developed around the scores of princely estates dotted around the subcontinent.

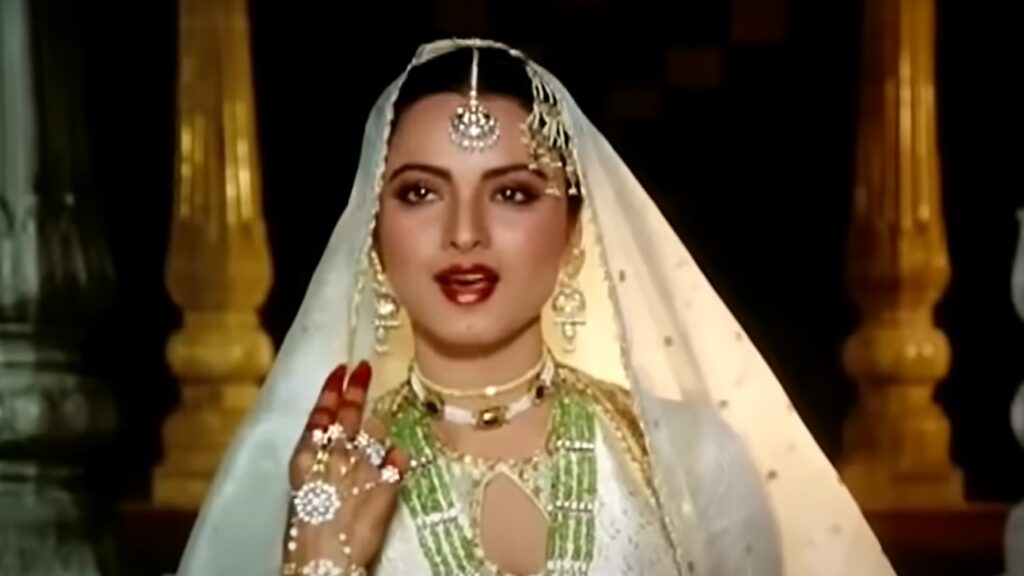

Based on the Urdu novel Umrao Jaan Ada by Mirza Hadi Ruswa, the movie tells the story of the eponymous Umrao Jaan, depicted by the legendary Indian actress Rekha.

A teenager kidnapped by a rival of her police officer father, Umrao Jaan ends up in the service of a kotha (salon) owner who teaches her the ways of the “tawaifs”, or female courtesans.

These were more than just female companions to Indian nobles interested in little more than sensual pleasure.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on

Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Under the tutelage of a khanum (lady), they were companions in the full sense of the word; singers, entertainers, poets and women of culture, who could hold their own in battles of wit and intellect.

In the movie, Umrao Jaan is educated as a tawaif and captures the heart of the Nawab Sultan, played by Farooq Shaikh.

What follows is a classic Bollywood love tale of lovers torn from one another, true identities revealed and honour lost.

Captivating its audiences with its genteel storytelling and an absorbing musical score anchored by the voice of Asha Bhosle, the film provides an acting masterclass supported by familiar faces like Naseeruddin Shah and Shaukat Azmi.

The courtesan in Bollywood

Umrao Jaan enjoyed a healthy share of prizes at film award ceremonies after its release and rightly enjoys its place in Bollywood canon, but its return to Indian cinemas represented more than just nostalgia.

For many Indians, it represents the age of “sensible Bollywood”, one that could filter Indian history through the prism of nuance, authenticity and taste; one that kept afloat an image of the tawaif untinged with idealism and preserved the institution’s cultural value.

The story of the courtesan and her royal lover is a frequently appearing trope of Indian cinema.

Each decade from the 1950s onwards produced its own epic.

Nandlal Jaswantlal’s 1953 offering Anarkali was based on Imtiaz Ali Taj’s 1922 play of the same name.

It tells the story of the Mughal prince Salim, who will later become the Emperor Jahangir, and his love affair with the semi-mythical courtesan Anarkali.

K Asif’s magnum opus Mughal-e-Azam (1960) is one of the most highly regarded movies in Bollywood history and is also a retelling of Salim’s affair with Anarkali.

In Asif’s version, Salim is brought to the point of rebellion against his father, the Emperor Akbar, which the latter duly subdues.

The price of Salim’s life is Anarkali’s own and the courtesan obliges by giving herself up for execution.

Kamal Amrohi focuses on themes of honour and shame in his intergenerational drama about tawaifs in Muslim Lucknow in his 1972 musical Pakeezah.

The tawaif in court culture

However, to limit debate on the function of tawaifs to the social consequences of their institution would be to rob them of their historical importance and reduce them to caricature.

Umrao Jaan stands out amongst others in the genre with its realistic narrative depicting court life in the princely state of Awadh in present-day Lucknow and eastern Uttar Pradesh.

A distinct salon culture emerged during the 19th century comprising a group of women who were elite courtesans.

The tawaif was a key element of court life and trained not just to entertain but to engage in conversation, and therefore reading and writing were key aspects of their training.

‘The courtesans were an influential female elite’

– Professor Veena Talwar Oldenburg

Such skills naturally brought them close to the men in power and allowed them entry into the world of court intrigues and power politics.

“At all Hindu and Muslim courts in the many kingdoms that made up the subcontinent before the British began to conquer them and displace their rulers, the courtesans were an influential female elite,” writes Professor Veena Talwar Oldenburg in her essay Lifestyle as Resistance: The Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow.

“The courtesans of Lucknow were especially reputable,” she adds.

According to Oldenburg, the institution of the tawaif gave a class of women an opportunity to challenge patriarchal restraints.

“I would argue that these women, even today, are independent and consciously involved in covert subversion in a male dominated world,” she writes.

“They celebrated womanhood in the privacy of their apartment by resisting and inverting the rules of gender of the larger society of which they are part of.”

Resistance against colonialism

The Umrao Jaan of cinema is a talented poet who, despite heartbreak and vilification as a “fallen woman”, is confident in her abilities.

Eventually, she takes a leap of faith to secure her independence and moves to Kanpur, another urban centre in colonial times, thereby severing her ties with Lucknow.

But expressing a spirit of independence in British India was not limited to Indian society but also against the colonial regime.

In the movie, the catalyst for Umrao Jaan’s departure from the court is Faiz Ali, a rebel at odds with the British over their annexation of Awadh into the Raj.

From the Achaemenids to the Mughals: A look at India’s lost Persian history

Read More »

While a minor plot point, the inclusion of colonial undertones alludes to the actual animosity between the British authorities and the tawaifs.

British chroniclers reduced the role of the tawaif to mere “dancing and singing girls”, as they are referred to in their records. Such a simplistic understanding naturally led to stigmatisation, vilification and eventual criminalisation of the institution as a form of prostitution.

Despite anti-colonial sentiment being high in upper class Indian circles, Victorian British prudishness filtered through and the intellectual class distanced themselves from the tawaif.

“Tawaif, the term used for a courtesan, has accumulated over time a moralistic value loaded with connotations in the popular mindset. It was equated to ‘whore’; forcing these women performers into silence,” writes Lata Singh, an academic at the Centre for Women’s Studies in Jawaharlal Nehru University.

“By the end of the 19th century tawaif had become an impolite word not used in genteel conversation,” Singh continues.

“The stigma later percolated into nationalistic discourse completely ignoring not only the intellectual, artistic aspect of a courtesan’s life but also their participation in the first war of independence, often covert, mostly non combative.”

One prominent example of tawaif resistance to British dominance in India was Azizun Nisa, who served as a spy and agitator within the ranks of the British Army’s Indian troops, known as Sepoys, during the Indian Mutiny of 1857.

This precedent, combined with their scapegoating for the spread of venereal disease amongst British troops, further entrenched their reputation for sexual licentiousness.

Invigorating the spirits: In search of India’s lost coffee culture

Read More »

In the aftermath of the war, Britain solidified its rule in India and sought to snuff out any demographic capable of sowing dissent.

It was a period marked by displacement and marginalisation for the tawaif.

Singh observes: “The collective impact of these regulations, the loss of court patronage and later material penalties extracted from the courtesans for their role in the 1857 rebellion were a severe blow to them and signalled debasement of an esteemed cultural institution.”

As India formed a nationalist movement led by mostly upper class and upper caste men and women, the perception of the tawaif remained trapped in a prejudiced, moralistic viewpoint.

That perception remained until early Bollywood’s revisiting of this essential Indian institution.

Even here, the approach was cautious, with any possibility of filmmakers being deemed sympathetic to the tawaif counteracted with endings where the women found themselves dead or as recluses.

That was, of course, with notable exceptions. Rekha’s character in Umrao Jaan survives tragedy with her dignity intact.

Hope that this would be a reversal in tawaif portrayals was short-lived, however, as Bollywood succumbed to the hypersexualisation of culture in the 1990s and 2000s.

The tawaif became the progenitor of the “naachganewalis”, a staple of modern Indian cinema, which loosely translates as “dancing and singing ladies”.

While emerging from the tawaif heritage, these women remained largely mute and in the background of Bollywood dance numbers, performing sexually objectified numbers in support of lead actresses.

The filmmakers of today may argue that this merely serves an audience’s need for escapism.

But a packed out theatre for Umrao Jaan’s re-release earlier this summer may suggest a longing for more rounded depictions of India’s women.