Recent US export control decisions imperil national security and threaten not only US artificial intelligence “dominance” but potentially many other emerging technologies critical to military programs.

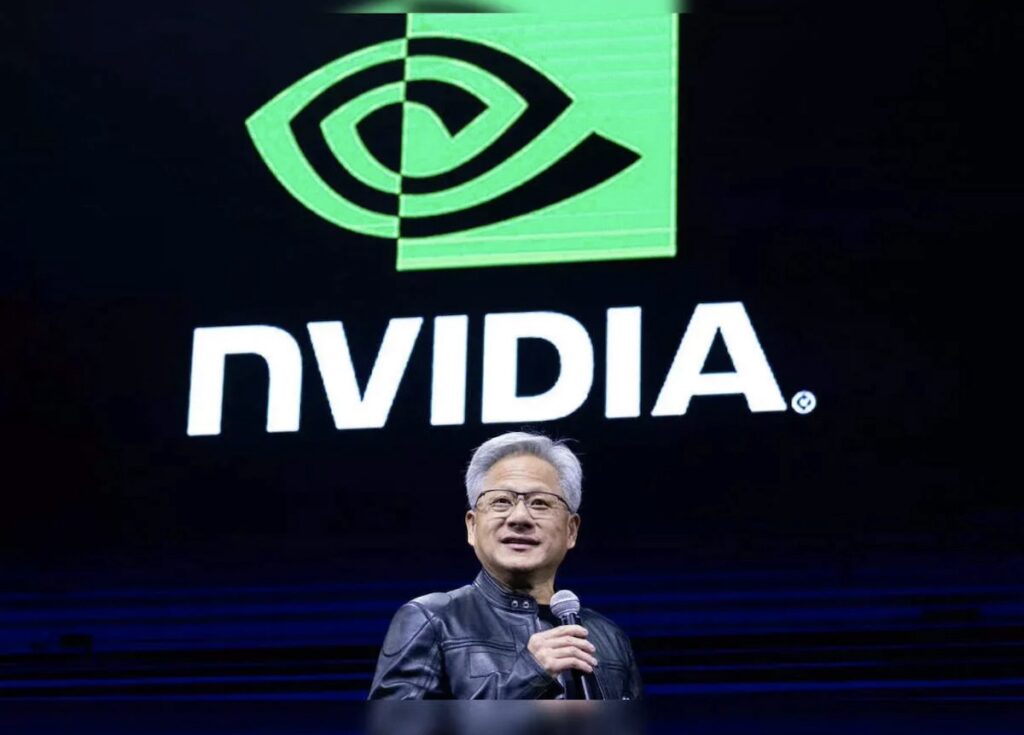

While legal US exports of AI-related semiconductors were blocked, China got at least US$1 billion worth of Nvidia-made chips illegally, mostly in “packages” of data-center-ready racks. The packages being sold in China are labeled as Supermicro, Dell and Asus. The chip packages, which include software, were sold at a 50% markup over US prices.

Meanwhile, the Financial Times reports that the Trump administration has decided to lift “aggressive” strategic export controls and has directed the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security to implement the new directive.

Under the US export control system, commercial exports, also known as dual-use exports, are controlled by the Department of Commerce. However, the Commerce Department is supposed to coordinate with the Department of State, Department of Defense, Department of Energy, Department of Homeland Security and US intelligence.

By law, US export controls support national security, lim supply and US foreign policy. These are broad categories. The US is also supposed to coordinate its export controls multilaterally, but since the dissolution of COCOM in 1994 and the weak substitute Wassenaar arrangement, very often the US resorts to unilateral export controls.

It is not clear what “aggressive” strategic export controls are, nor is it clear how they impact the interagency deliberative process. One presumes that the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Export Controls will try to come up with some sort of export licensing guidelines to cover the White House directive. Neither the Commerce Department nor the other involved agencies apparently played any role in the White House directive.

Prior to the White House decision, Trump previously told Nvidia it could restart chip exports to China, an apparent quid pro quo in which China released rare earth exports to the United States. Twenty former US officials say allowing Nvidia to export chips to China was a strategic misstep.

The latest White House move, lifting “aggressive” strategic export controls, is designed to facilitate trade negotiations between Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping. Looked at objectively, Chinese export restrictions trumped Trump (pun intended).

Some expected that Trump would go to China in September when Russian President Vladimir Putin is also expected. However, it appears that the idea has been nixed, and Trump won’t meet with Xi and Putin together and will go to China later in the Fall, probably after the APEC meeting in South Korea. News reports say that China and the US are working on an agenda and a date for a high-level meeting.

The immediate impact of removing “aggressive” export controls will be on AI-relevant technology. The Trump administration has released an AI Action Plan. The plan calls for removing “red tape” that delays AI investments and initiatives, investing more in AI and boosting government investment, especially by the Defense Department. It also describes the US effort in AI as a “race” like the “space race” in the past and seeks “American dominance” in AI.

The latest decisions on export controls, and specifically on Nvidia, compromise the AI Action Plan. They are totally incompatible.

The lifting of export controls on Nvidia, which is the premier component in AI data centers, and the subsequent order to lift “aggressive” export controls, not only subverts the billions of investment already made in AI but also leaves uncertain what other critical US technologies will be sold off to China.

There is little doubt China is aggressively pursuing AI and is investing billions in the effort. According to investment bank Morgan Stanley, China is a sleeping giant that is now awakened and seeking global AI dominance by 2030. It is important to note that US companies like Nvidia will now directly assist China by sharing know-how and technology.

There are many sensitive emerging technologies that are quite important and in many cases sensitive to US national security. The chart below illustrates some of them:

The immediate question is whether the latest policy guidance from the White House includes any or all of the emerging technologies? The above chart was published to highlight what the Trump administration originally wanted to curtail using export controls.

It is normal whenever new US export controls or guidance is proposed for the Commerce Department to publish the policy for comment before it is approved. In the comment period, the public (most often industry) comments on the proposed rule.

It is far from clear if the Commerce Department will publish guidance for the latest policy change, but it should do so. Moreover, it should explain the national security implications as it understands them.

There is also the question of interagency coordination, a non-trivial part of the US export control process. Will the Defense Department and other agencies (especially the intelligence community) be consulted, or will the Commerce Department ignore the other agencies?

Typically, the Defense Department concerns itself with the impact of approving export licenses that might undermine national security and the military mission. Beyond that, many of the emerging technologies are critical to US defense systems and represent areas where the Defense Department has invested billions of dollars.

The latest decisions contradict the AI Action Plan and potentially compromise export control protection of critical emerging technologies. In turn, the decisions damage US national security as defined, in part, by the administration itself.

Stephen Bryen is a special correspondent to Asia Times and former US deputy undersecretary of defense for policy. This article, which originally appeared on his Substack newsletter Weapons and Strategy, is republished with permission.