Hot summers are nothing new for much of the United States, but the combination of heat and humidity has taken on a truly antagonistic role this year, pushing us closer to our melting points in an already uncomfortable season.

Dew point temperatures – a measure of how much moisture is in the air – have soared to sauna-like highs over and over. It’s another way a climate heating up from fossil fuel pollution is changing summer as we know it.

A warm atmosphere soaks up water like a sponge, driving both air and dew point temperatures higher than they’d be in a cooler world. “Summertime heat that’s being boosted by climate change is now also getting this extra piece,” said Shel Winkley, a meteorologist with the non-profit research group Climate Central. “It’s like a one-two punch.”

For nearly half the country, this summer’s duo of heat and humidity has been record-breaking so far: June through July marked the muggiest start to the season in more than 40 years, based on a CNN analysis.

Here’s what’s behind this summer’s especially soupy start.

The eastern half of the US is typically home to the most muggy, humid conditions in the country, but this summer has been extreme.

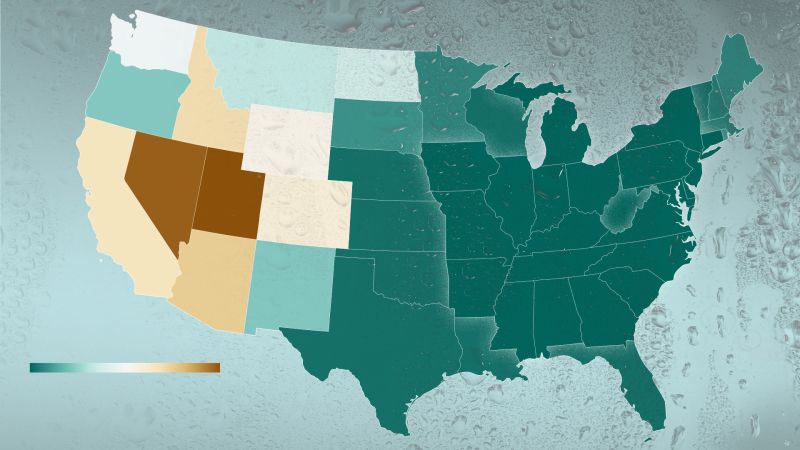

Through July, 22 states from the Mississippi Valley to the East Coast have notched their muggiest start to summer since 1981, when the dataset of dew point temperatures used for CNN’s analysis began. It’s been the second-most humid summer for the US as a whole in the same timeframe.

Higher dew points mean there’s more moisture in the air, and when there’s more moisture in the air, it feels more humid. Dew point temperatures are always the same as or lower than the air temperature.

A summer dew point of 70 degrees, for example, means the air feels pretty sticky and uncomfortable. Crank that closer to 80 degrees and the air feels thick, soupy and miserable. On the opposite end, a summertime dew point in the 40s or 50s can feel downright desert-like.

Relentless summertime humidity is par for the course in many southern states like Mississippi and Alabama, thanks to their proximity to the warm, moist air over the Gulf, but the last two months have been far past the norm.

Dew points have consistently been at least in the low 70s throughout this summer in much of the South. They climbed into the 80s multiple times during the late-July heat dome, pushing the heat index – how hot it actually feels – past 110 degrees at times.

The Midwest is another notoriously humid region in the summer. In states like Iowa and Illinois, there’s a surprising agricultural contributor: Corn. The crop covers much of the farmland in these states and “corn sweat” can boost dew point temperatures all on its own. But this summer has so far been much more muggy than corn can influence single-handedly.

Early summer conditions in the West were much more mixed. Nevada and Utah had one of the least humid starts to summer on record, cut off from most of the moisture flowing to areas farther east and anything heading inland from the Pacific Ocean.

California was much more middle of the road. Even with its proximity to the Pacific, sea-surface temperatures closer to shore were cooler than normal for much of June and July. Colorado’s dew points were also average as the state avoided the moisture onslaught that unfolded farther east.

What’s happening both in and over nearby oceans is to blame for this summer’s excessive mugginess.

Sea surface temperatures in the Gulf, the Caribbean and the Atlantic have been warmer than normal – and in some cases, much warmer – this summer. While temperatures aren’t at the record-breaking levels that marked long stretches of 2023 and 2024, the fingerprints of climate change are still all over this summer’s ocean heat.

For example, hotter than normal sea surface temperatures in the Gulf and in the Atlantic off the Southeast coast last week were up to 500 times more likely because of climate change, according to Climate Central’s Climate Shift Index, Winkley noted.

The warmer oceans get, the more moisture evaporates into the atmosphere. A warmer atmosphere behaves like a sponge, soaking up and then transporting what moisture the ocean releases.

Abnormally moist, hot air has been flowing north out of the tropics into almost all regions east of the Rockies all summer — and really for much of the year.

It’s tied to a semi-permanent area of high pressure that meanders over the Atlantic Ocean called the Bermuda or Azores high, Winkley explained. In the summer, the high generally parks over the western Atlantic and is perhaps best known for how it can steer Atlantic hurricanes toward the US – but that same mechanism also delivers tropical air.

The Bermuda high was stronger than normal in June and was also significantly stronger compared to the same time in 2023 and 2024, according to data from Columbia University. In its stronger state, the high has sent frequent pushes of waterlogged air into the US that made dew points skyrocket and loaded the atmosphere with moisture to fuel flooding storms.

Muggy, more humid air is driving up the heat index and that’s a dangerous trend: When it’s too humid, it’s much harder to cool off naturally.

Really humid heat cancels out the benefits of sweating and puts a much higher strain on the body. This leaves people – especially those without access to air conditioning – much more susceptible to heat exhaustion and heat stroke.

High dew points also prevent air temperatures from dropping considerably overnight, keeping nights warmer than they should be. Nighttime air temperatures are already taking the hardest hit from climate change – warming faster than daytime highs – and when nights don’t cool down enough to offer relief for overheated bodies, it’s a compounding disaster.

“A lot of us are very lucky that we get to go from our air-conditioned home, to our air-conditioned car, to our air-conditioned workplace, but that’s not everybody,” Winkley said.