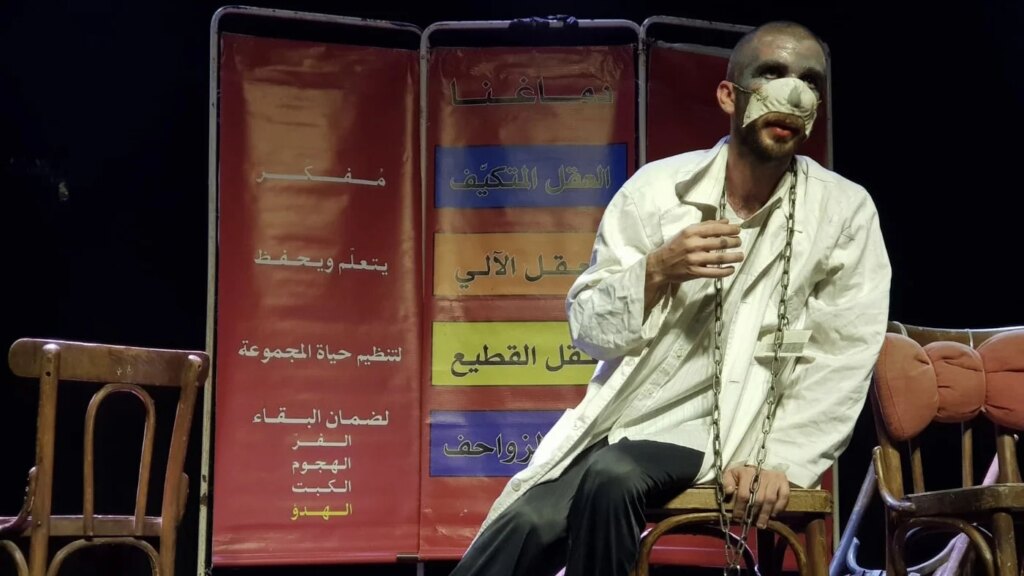

On stage in a theatre in London’s Kings Cross, a disturbed man, his face partially covered with tape and a mask, explains a thesis about the human brain to the audience.

Waseem Khair, the Palestinian actor and filmmaker, wears a doctor’s white coat, and a long key chain hangs around his neck. His movements and his appearance are clown-like – both tragic and comic.

He explains in Arabic how the primitive, lizard part of the brain, the 400 million-year-old amygdala, still controls much of the brutal, instinctive behaviour of humans – “the strong kick ass, the weak lick ass”.

“It is not the world which makes us suffer, but the way that we look at it,” he says.

He uses the idea of Tarzan, a big neighbourhood bully who uses strength and violence to dominate the jungle – the obvious parallels with Israel and its actions against Palestinians and other Arab countries do not need to be made explicit.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on

Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

He compares the “law of the strongest”, based on hierarchy and brute force, to the uselessness of the male nipple, an obsolete evolutionary hangover that still dominates us as a species.

The performance at Teatro Technic, supported by the PalArt Collective, is part of an international tour of his long-running one-man show, In the Shadow of the Martyr, which has recently toured Lebanon, Tunisia, Morocco and France.

Khair plays Nidal Abdelatif, a former medical student from Palestine who goes to Sarajevo to study neuroscience. Then, his brother carries out a martyrdom attack in Israel- a suicide attack- and in reprisal, Israel demolishes his family home.

Abdelatif is forced to give up his studies and return to look after his parents in the Jalazone refugee camp, where he works as a doorman.

“Nidal was supposed to come back to Palestine as a hero, as a doctor who could heal people, but he is overshadowed by the martyrdom of his brother,”Khair explains to Middle East Eye.

“For the Palestinian people, sacrificing your life for your homeland is the highest thing that you can do in life,” he says.

Legacy of Francois Abu Salem

The play is based on the neuroscientific research of the French-Palestinian theatre pioneer Francois Abu Salem, which he studied in Paris in the 1970s.

Abu Salem, who grew up in Palestine and Lebanon, was a founder of al-Hakawati, Palestine’s first national theatre, in Jerusalem in the early 1980s.

‘The Israelis don’t want the world to see us Palestinians as creatives or as artists, they only want the world to see us as brutal, human animals’

– Waseem Khair, actor

In The Shadow of the Martyr was his final play before his suicide in 2011. Since then, Khair, who worked with Abu Salem at al-Hakawati theatre, took on the work as his own and has performed it more than 500 times across Palestine and Israel, as well as on tour.

“I am still discovering new aspects of the character each time I perform it. Even here in London it changed during the three performances,” he tells MEE, as translated by his producer.

In the play, the difference between the two Palestinian brothers symbolises the two parts of the human brain.

Neuroscience tells us that besides the amygdala, there are other more recently evolved mammalian parts of the brain, including the neocortex and prefrontal cortex, that relate to cognition and conscious thoughts, language, sensory perception, self-control and regulation of social behaviour. In other words, those parts of our brain that we think of as most human.

They give us curiosity, the ability to empathise, and these are the parts of the brain that can save us if we cultivate and use them, Abdelatif tells us.

In the story, in part based on real-life incidents, Nidal’s brother’s attack is in part revenge for his mother, who worked in an Israeli factory and lost her eye, but was denied compensation as a Palestinian under the apartheid system because she is not an Israeli citizen.

Palestine 36: Annemarie Jacir’s epic is a lesson in anti-Hollywood history

Read More »

“Not only couldn’t Nidal finish his studies, he couldn’t save his brother from this mentality. He lost his meaning, his character, his personality, living his life in the shadow of his brother’s martyrdom.”

Abdelatif, a sad, psychologically disturbed clown, acts playfully with the audience, even touching one woman’s face, swinging his key chain violently, moving erratically, lifting and dropping chairs in wild movements.

The play has a tragic and disturbing quality; we sense that this eccentric behaviour is an acting out of depression and trauma.

Speaking of the appearance of his character, Khair says: “if we look at the bodies of Palestinians in general, we look at bodies that are fragile, they are demolished.

“These bodies are the result of the psychological impact that the occupation is putting on the Palestinian people, in the most extreme cases, such as those coming out of Israeli prison.”

Art as resistance

Khair himself has been arrested and persecuted by the Israeli authorities dozens of times over the years because of his artistic work as a theatre maker and film maker.

All of this confirms the continued relevance of the play, says Khair.

Superman: Palestinians are not waiting for a white superhero saviour

Read More »

“The Israeli brain really knows that our struggle and our wars and our conflict is not only on the land; it is a war of narratives, and they’re very much aware that theatre and arts in general are a way for us to tell our honest narrative, and this is why they are always attacking it.”

Khair says resistance need not be armed or violent, and culture is key.

“We as Palestinian artists believe we are resistance fighters; we don’t hold weapons, we hold our texts, our cameras and our stories, in order to reach our liberation.”

A planned new tour of the show in Palestine has been blocked by the Israelis, because of the title.

“The martyr now is a very dangerous name for Israelis,” he says.

All theatres in the occupied West Bank, Jerusalem and Israel have told them they can’t host the show due to its title.

Conditions for artists in occupied Palestine and in Israel are as difficult as they have ever been, he adds.

“Since the beginning of Palestinian theatre in the 60s and 70s until today, this is the hardest period that Palestinian theatre has ever endured. There is oppression for the Palestinian arts in general, not only theatre.”

‘We as Palestinian artists believe we are resistance fighters’

– Waseem Khair, actor

On 22 November, during a performance of folk songs by around 50 children at al-Hakawati Palestine National Theatre, Israeli intelligence forces raided the venue, coming onto the stage to forcibly shut down the show.

It was an example of the way in which the Israeli government views Palestinian arts, even traditional songs performed by children, as a direct threat to the occupation, says Khair.

“Our Palestinian theatres are invaded and closed forcibly, like what happened to al-Hakawati theatre in Jerusalem, and there are many other theatres that are being closed forcibly.

“Also during this genocide we have lost many, many beloved artists, filmmakers and theatre makers in the West Bank and in Gaza.

“This is a clear sign that the Israeli occupation understands very clearly that art is a tool for resistance, and this is why they are trying to delete it all the time.”

Warning to the world

This harsh reality brings us back to the play’s core theme of the dominance of the primitive brain in the Palestinian reality imposed by Israel.

Khair says: “unfortunately, the Israeli mentality is working on the brutal part of the brain that we talked about before.

“It scares them so much, the artistic part of the brain that uses creativity in order to be liberated.

“I don’t want to see anyone here in 5 minutes.”

Israeli intelligence forces stormed the Hakawati Theatre, also known as the Palestinian National Theatre in East Jerusalem, and abruptly shut down a children’s performance, threatening the audience with just five minutes to leave.… pic.twitter.com/llDo6OHpIr

— Middle East Eye (@MiddleEastEye) November 24, 2025

“The Israelis don’t want the world to see us Palestinians as creatives or as artists, they only want the world to see us as brutal, human animals in order to justify their existence in the region.

“And this didn’t start on 7 October, it has been going on for a very long time.”

He says the play is a universal warning for people to see how our brutality controls our actions and how we are unable to control it.

“This is a Palestinian play but at the same time it talks to the whole world, it is meant for everyone to talk and think about.”