CNN

—

While a British summer is never a guarantee of hot weather, there’s one thing you can be sure of: Brits will be going to the beach.

For centuries, and in all kinds of weather, the British have licked ice creams, strolled piers and dropped coins in arcade games at the seaside. The town of Scarborough on England’s North Sea coastline, widely considered Britain’s first seaside resort, has been welcoming tourists to its restorative spa waters for around 400 years.

“The concept of going to the beach for leisure was something that the British invented,” architectural historian Kathryn Ferry, told CNN, in a view shared by many experts. “It’s part of our nation’s story, our island’s story, and there is a sense that it is important for our identity. British people have that need to go to the coast and smell that sea air,” she said.

While affection for the British seaside has, much like the tides, surged and fallen over the 20th century, it has been an enduring source of inspiration for artists including the prolific photographer Martin Parr, whose distinctive and radical portraits explore social class and leisure in the north of England in the 1980s, and multidisciplinary artist Vinca Petersen, whose work depicts youth and subcultures at the beach in the 1990s.

Two new photography books this year explore the unique character of the British beach.

In Ferry’s new book, “Twentieth Century Seaside Architecture: Pools, Piers and Pleasure Around Britain’s Coast,” postcards are used to explore how societal and cultural attitudes interacted with the architecture of the British seaside. “I love the mundaneness of these postcards,” she said. “They are historical documents, but are flimsy and throwaway.”

A combination of illustrations and photographs show the grandeur of classical and art deco designs of the interwar years, through to the post war buildings inspired by the 1951 Festival of Britain, and the concrete brutalism of the 1960s and 1970s. “Seaside resorts were competing with each other, and that meant that if one place had a new facility that was going to give them a step up with tourists in terms of attractions, then lots of other places would follow,” said Ferry, referring to architectural features such as lidos, pavilions, bandstands and distinctive roof shapes commonly found at British seasides.

Ferry isn’t the only academic researcher beguiled by these snapshots of another era. A little over a decade ago, Karen Shepherdson, the co-author of a 2019 book on the subject, “Seaside Photographed,” also founded the South East Archive of Seaside Photography, which houses collections of commercial seaside photography dating from 1860 to 1990.

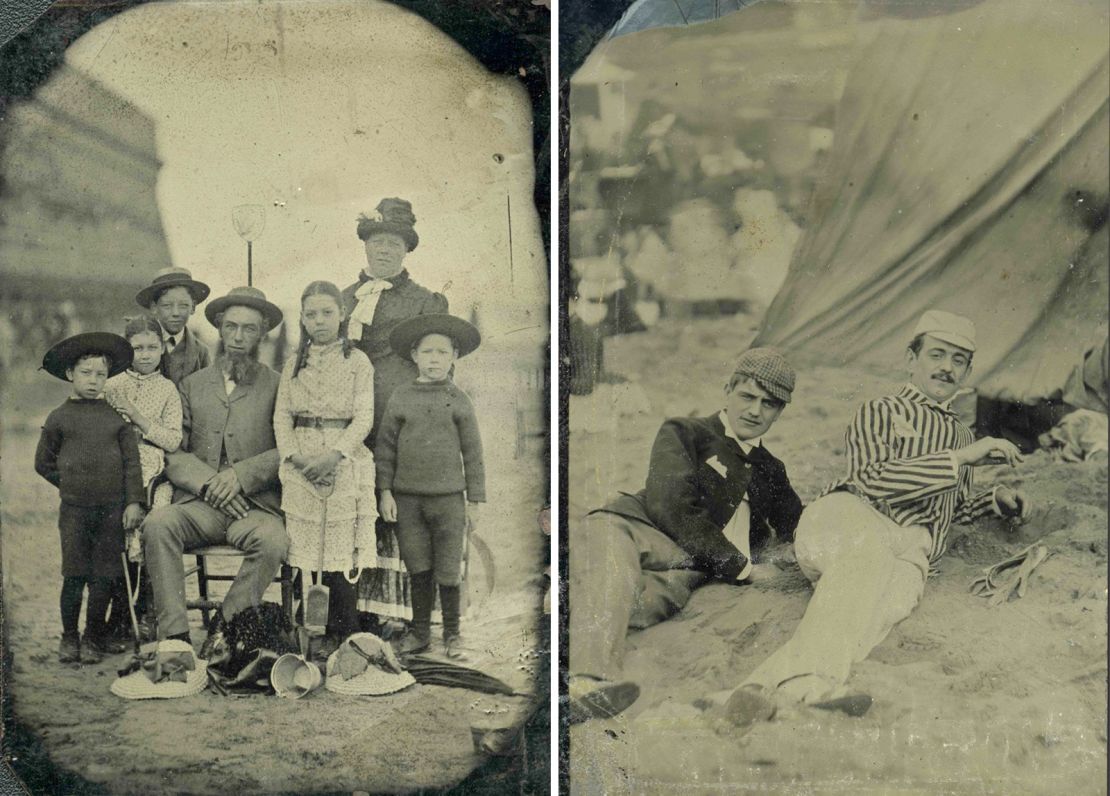

Shepherdson’s own research interest is in ‘walkies’ — images made of people walking down the promenade that were captured by a commercial photographer and printed onto a postcard. The tradition emerged in the 19th century, a time when people generally did not have easy access to cameras or could afford portrait painting. Travelling photographers offered their services to families walking along the beach, who could take home a keepsake photograph in just a few minutes.

Shepherdson’s callout for walkies from the 20th century led to an influx of contributions to the archive from people sharing their personal postcards. “People would hold them like relics, and touch them as they were telling us their stories,” said Shepherdson. “These, in essence worthless photographs, are priceless and powerful.”

With the emergence of international budget holidays and cheaper airfare prices, the British seaside holiday fell out of fashion in the 1970s and 1980s. In some towns, seaside tourism declined and even collapsed, with decades of neglect creating a chasm between extreme poverty and wealth. These long-term existing inequalities meant coastal communities were particularly vulnerable to the impact of Covid-19 lockdowns, with areas experiencing some of the largest drops in local spending as well as the highest rises in unemployment in the country in 2020.

However, restriction of movement during Covid-19 also led to an increase in staycations and domestic holidays at the seaside. In some cases, beaches even became severely overcrowded. A resurgent interest in the seaside has also led to gentrification and exacerbated inequalities in some areas; house prices in the southeast coastal town of Margate for example more than doubled in the decade from 2012 to 2022. Recent research has also shown that young people in coastal communities across the UK are three times more likely to have a mental health condition than peers in other parts of the country.

For London-based photographer Sophie Green, whose projects were forced to pause due to lockdown restrictions in 2020, the seaside became a vital location to create new work. Five years later, her ongoing project “Beachology” has taken her to several beaches across the UK, offering a contemporary portrait of British life at the seaside. “I’ve always been drawn to distinct social settings where people are defining a sense of themselves, or how particular social customs or rituals are played out,” said Green, whose latest photobook “Tangerine Dreams” was published earlier this year. “The beach is another iteration of that: a distinct place where people are a version of themselves that they might not be in other spaces.”

For Green, the beach is a prime site for people-watching and observing the intimacies of everyday human interactions. “The textures and the environment, the seascapes and the colours are so specific — whether that be the funfairs with the bright, gaudy, lurid colours, or the casinos with their amazing typography — there’s a distinct aesthetic to those spaces which you would never find anywhere else in the world,” she said.

Green’s project has taken her to beaches spanning Hunstanton –– known locally as “Sunny Hunny” –– in Norfolk, Blackpool with its iconic tower and Skegness, which was home to the first Butlin’s holiday resort camp built in 1935. “Everyone goes to the beach with the same agenda, and there’s something quite special about that, where people are united, can be in nature and can feel liberated,” said Green.

In recent decades, art has also been used to attract visitors looking for cultural experiences alongside their beach visits, said Ferry. In 1993, the Tate Gallery, St Ives, opened in the south west coastal region of Cornwall. The Turner Contemporary and Hastings Contemporary galleries both opened on the south east coast in 2011 and 2012. Other public art initiatives include sculptor Damien Hirst’s site specific work ‘Verity’ that stands at Ilfracombe, North Devon, and The Great Promenade Show; a series of public art installations along the Blackpool promenade that has run since 2001.

While the pandemic offered a kind of enforced rediscovery of the seaside, it hasn’t quite had the sustained pull and boost for local tourism that some hoped it might. But whatever the economic –– or weather –– forecast, the British will always have the beach. “Times are hard globally and financially, and I think the seaside offers us a place of relative democracy,” said Shepherdson.

“When we’re on the beach, we’re stripped down. It becomes a very democratic space, and by and large, a free space where you don’t have to pay,” she added “There are very few actual lived experiences that we might think of in that shared way.”