In the aftermath of 7 October and ensuing Gaza genocide, major film festivals in Europe and the US have refrained from directly addressing the subject.

Most programmers opted to express their position through film selections, often by championing films with themes sympathetic to Palestinians.

Others have attempted to maintain “balance” or refrain from engaging with the subject altogether.

No director of any of the world’s top festivals has dared to make an explicit reference to Gaza over the past 22 months – until now.

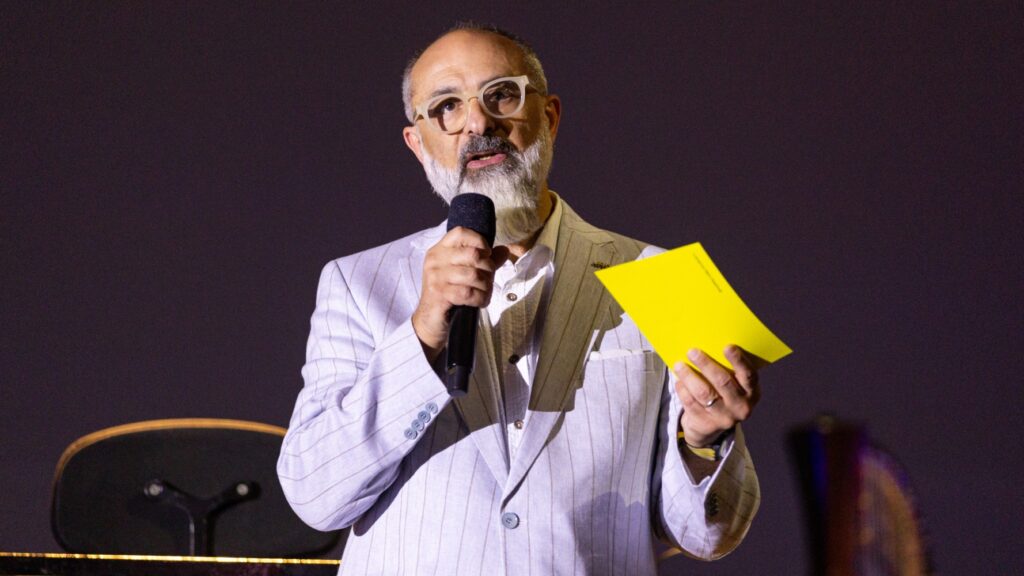

On 6 August, the opening day of the Locarno Film Festival (which ran until 16 August) in Switzerland, Italian artistic director Giona A Nazzaro broke the silence to become the first western festival head to explicitly express solidarity with the Palestinian people.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on

Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“As a community and as individuals, we have a duty to keep our eyes open, especially towards places where suffering is a daily struggle, and therefore to denounce the intolerable destruction of Gaza and the terrible humanitarian tragedy that is afflicting the Palestinian people with the violence of bombs and famine,” Nazzaro told the 8,000 attendances of the Piazza Grande, the biggest movie venue in Europe.

This was an unprecedented statement that few saw coming.

The ceremony was preceded by an impassioned peaceful protest by local activists lobbying to end the Gaza genocide.

Nazzaro’s blistering, heart-felt speech was a reflection of the growing frustration and rage of a certain sector of a film community no longer capable of carrying the moral burden of silence in the face of injustice.

With that speech, Nazzaro raised the stakes for other directors.

All eyes will now be on Venice and Berlin whose directors are not expected to follow Nazzaro’s lead.

The director told me that his position was fully backed by the festival’s president and Swiss billionaire, Maja Hoffmann, whom he described as “wonderful”.

Various personnel in the festival did inform me, however, that some sponsors were not pleased with Nazzaro’s speech.

While no pressure has been exerted on the Italian critic to “tone it down” – partially due to public backing of Nazzaro’s politics – delivering it was always going to carry a risk of backlash.

With Hasan in Gaza

The Arab selection of the 78th Locarno was as overly political as Nazzaro’s speech. Topping the lineup was With Hasan in Gaza, the latest documentary by Palestinian conceptual filmmaker Kamal Aljafari.

The sixth feature by the man behind A Fidai Film is based on three recently rediscovered MiniDV tapes documenting his two-day road trip in Gaza in November 2001, a year after the ignition of the Second Intifada.

Aljafari’s visit at the time was propelled by a search for a Gazan inmate with whom he shared a cell in an Israeli prison in 1989.

The particularities of their relationship and reasons behind the director’s detention is only revealed in the concluding act of the film.

Apart from inserting a near-invisible score, Aljafari doesn’t tamper much with the footage, preserving the unpolished, wide-eyed vision of his younger self.

Our knowledge of the ongoing genocide haunts every scene, every frame of the film.

Throughout his journey from the north to the south of the territory, the director offers us bracing vistas of bustling markets, light traffic, unemployed men populating coffeeshops, and the ruins of buildings destroyed by the Israeli army.

Historicism is the driving force behind the project. The walls of the 2001 Gaza are covered with Arabic graffiti: The slogan “Al-Qassam is the solution” is glimpsed on a few occasions, while others celebrate “the martyrdom of Gaza”.

Collectively, these randomly inked scrawls act as a cry by silenced people pleading to be heard and seen.

The early 2000s music of Egyptian pop star Amr Diab – the Arab world’s biggest singer of the past 35 years – can be heard from the speakers at fast-food joints, imbuing these ostensibly uneventful sights with an aura of provisional, simulated normalcy.

The raw nature of the footage – deliberately amateurish compositions shot mostly via hand-held camera – pinpoint a time when the image held more power, more significance, more truth, more meaning, than it does now.

Our knowledge of the ongoing genocide haunts every scene, every frame of the film.

The fates of the Palestinians of Aljafari’s Gaza are unknown. Some may still be alive; some may have left; others may have been starved to death and killed under the rubble.

Gaza has endured plenty of pain, grief, oppression, and destruction, Aljafari emphasises, but it never lost its humanity, its joy, its resilience.

Aljafari captures this world so vividly, so tenderly, so unassumingly in his futile search for a piece of himself forever lost in detention.

History repeats itself, but in the case of the current genocide, history has stood still, giving way for documents such as With Hasan in Gaza to provide a time capsule of a place that no longer exists.

It’s a remarkable work, and the standout Arab film of Locarno 2025.

Still Playing and Tales of the Wounded Land

Israel was the unequivocal villain in many of this year’s offerings, including Mohamed Mesbah’s medium-length documentary Still Playing, about a young West Bank father coping with Israeli raids by developing video games; and Jean-Stephane Bron’s incendiary Swiss mini-series The Deal, a loose dramatisation of nuclear talks between the US and Iran, which Switzerland hosted in 2015.

More pronounced and less effective was Tales of the Wounded Land, the latest documentary by Lebanon-based Iraqi filmmaker Abbas Fahdel, who earned the best director award.

A chronicle of the aftermath of Israel’s 2024 attack on southern Lebanon as witnessed by the director and his Lebanese wife, painter Nour Ballouk, Fahdel provides a first-hand perspective of the terror and devastation inflicted on residents of the South in the immediate period that followed the 1 October strike.

Fahdel meticulously records the dread and horror of the start of the attack: The shaken curtains of his house, the blaring noise of the explosions, the thud of collapsing residential buildings, the unnerving warning for evacuation blasting from megaphones, his daughter’s bafflement over the unfolding, incomprehensible chaos.

A barrage of images of the wrecked structures punctuates testimonials from Lebanese southerners striving to resurrect their devastated land.

Fahdel’s intentions are undeniably sincere, not only in putting a human face to a southern Lebanon long positioned as nothing more than a Hezbollah enclave by western media, but in celebrating the efforts of a battered community of pharmacists, artists and booksellers coming together to restore their home.

At 120-minutes though, Wounded Land is at least one hour too long.

Recurrent, indistinguishable images of the rubble quickly grow redundant and wearisome as viewers gradually grow desensitised towards these otherwise disheartening vistas.

The testimonials also suffer from a similar sameness, habitually outstaying their welcome as the interviewees repeatedly echo each other’s sentiments.

More problematic is the director’s ethically questionable decision to film his own family.

Prying sequences of his little daughter’s reaction towards the spiraling violence reek of irresponsibility and voyeurism.

Fahdel is one of the Arab world’s most mature filmmakers, but Tales of the Wounded Land is certainly not his finest hour.

Some Notes on the Current Situation

Less ambiguous but equally lacking was Some Notes on the Current Situation, the new feature by Israeli filmmaker Eran Kolirin of The Band’s Visit fame.

His latest production, made on a shoestring and featuring a cast of students, comprises six separate episodes impregnated with scathing commentaries on Israeli society.

Shot in black and white, the film kicks off with a bang. A military officer trains his soldiers for a Netflix film designed to give the state a facelift, the kind of output festivals were carelessly programming prior to 7 October.

The word “apartheid” is used to describe the treatment of Arabs in Israel, as buzzwords like “international terrorism” and “fucking Iranians” are thrown in the Full Metal Jacket-like training lecture.

The opening episode is the strongest segment of a picture laced with paranoia, rage, and an abiding sense of doom.

Alas, it fizzles soon afterwards as subsequent episodes fail to maintain the momentum and prowess of the opening sequence.

They range from lo-fi sci-fi to folk tales, which come off as too understated, too esoteric, and too insular to leave an impact.

Kolirin depicts Israel as a narcissistic, naval-gazing society, too self-indulgent to change.

The avoidance of Gaza and Palestine in the proceedings will raise eyebrows, yet it’s also part of the project’s design to underline the society’s self-centredness.

Some Notes on the Current Situation is not without merits, but overall, it is a missed opportunity by one of Israeli cinema’s staunchest critics.

Irkalla, Exile and Cairo Streets

Away from Palestine and Israel, acclaimed Iraqi director Mohamed al-Daradji (Son of Babylon) delivers his weakest work to date in Irkalla: Dreams of Gilgamesh, a coming-of-age story about a couple of young boys toiling to leave an impoverished Baghdad ravaged by the mass protests of 2019.

Self-importantly bleak and exasperatingly formulaic, Irkalla is the bastard child of Capernaum: a regressive piece of misery porn replete with child labour, terrorist plots, and underage prostitution.

The 2019 protests, which Daradji strangely refrains from taking a position on, transpire as nothing more than a backdrop for a tale of juvenile delinquence.

Venice Film Festival: Jewish director Sarah Friedland praised for Palestine solidarity speech

Read More »

The casting of the Islamist gang leader as a disrupter of the protests oversimplifies the wide-ranging and conflicted interests of Islamist groups in the uprising.

The final dedication to the “children of war” reeks of insincerity and contrivance.

More ambitious if equally contrived was Tunisian Mehdi Hmili’s sophomore effort Exile, a film too enamoured with its bold visual style to develop an emotionally resonant plot.

Instead it offers a knotted narrative about a steel worker’s vengeful quest to uncover the mystery behind a factory explosion linked to a scheme to privatise his plant.

The best non-Palestinian title of the selection was Cairo Streets, a 20-minute short by Moroccan filmmaker and best-selling novelist Abdellah Taia that charts his trip to Cairo in the mid-noughties to track down the Egyptian lover he left behind.

A deeply intimate, affectionate love letter to a pre-2011 revolution Cairo, Taia casts his queer gaze to reveal a city entrenched in contained chaos, on the brink of profound and shattering transformation.

The people, places, and sights he shows are permeated with a disarming tenderness that encapsulates the contradictory essence of the Egyptian capital: the kindness and violence; the warmth and hostility; the jadedness and childlike optimism.

A cameo by the late legendary filmmaker Youssef Chahine, an icon of queer Arab cinema, transpires as a sly homage to the queer side of the city.

Mektoub, My Love: Canto Due

And then there was Mektoub, My Love: Canto Due, the most talked-about film at Locarno and the latest entry in the notorious film series by French-Tunisian Palme d’Or winner, Abdellatif Kechiche (Blue is the Warmest Color).

Since his Cannes win, Kechiche has been embroiled in a series of scandals: accusations of sexual assault; allegations by Blue stars Lea Seydoux and Adele Exarchopoulos of exploitation and maltreatment; and reports of coercing reluctant actors with alcohol for sex scenes in the second Mektoub pic.

On a cinematic level, Kechiche’s predatory, aggressively masculine gaze that constantly surveys the bodies of his young actresses became no longer permissible in the post- #MeToo age.

Kechiche no longer has anything remotely fresh or noteworthy to say about the Arab experience in France

His last installment of Mektoub, which this writer found repulsive, was so widely panned that it was never released.

The Mektoub series follows the uneventful exploits of Sete-residing second-generation French North-Africans over a series of summers in the 90s.

A grand celebration of both the hedonism of the pre-digital, pre-PC age and the communal spirit of extended North African families, Kechiche relays this discourse in its fullness in the first 30 minutes of the first film.

There’s little to nothing else in the next seven hours of the series.

In Canto Due, Kechiche at last retires his predatory gaze, banishing his notorious close-ups of women’s assets, to create the kind of enveloping lived-in experiences that made his name.

The third film sees the series’ protagonist, Amin (Shain Boumedine), dropping out of medical school to pursue a career in filmmaking.

Lady Luck smiles upon him when Hollywood star Jessica (newcomer Jessica Patterson) and her middle-aged producer husband Jack (Andre Jacobs) descend on his family’s restaurant one fateful night for its signature couscous.

His cousin Tony (Salim Kechiouche) convinces Jack to read a sci-fi script by Amin. Surprisingly, Jack loves the script and decides to take on the project. But greed, Hollywood’s anti-artistry, and perilous carnal desire come to stand in the way of Amin’s dreams.

Canto Due is undeniably entertaining and immersive; an addictively watchable drama populated by pretty people falling in and out of love against the backdrop of endless French summers.

Make no mistake though, Canto Due remains as light as a feather; a diverting wish-fulfillment fronted by a maddingly passive, soulless protagonist.

Kechiche no longer has anything remotely fresh or noteworthy to say about the Arab experience in France.

His latest is a vastly sensorial experience, albeit a derivative, less scandalous one that adds nothing new to a series – one of the most pointless in film history – that has long run its course.