CNN

—

Visitors to European galleries with an interest in pioneering women artists will have plenty of choice this summer, with a series of new exhibitions featuring some of the biggest names in 20th century art.

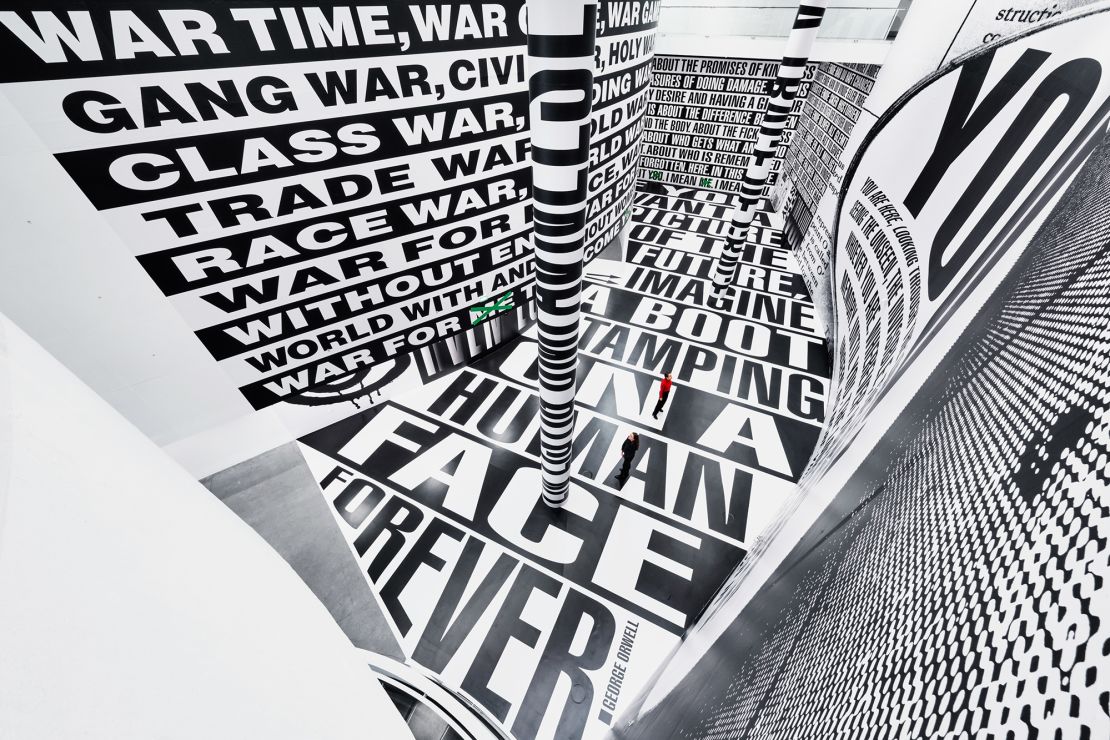

Fantastical sculptures and dreamlike drawings by the late French artist Louise Bourgeois, famed for her towering spiders, are on display at the Courtauld Gallery in London. Elsewhere in Spain, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao is hosting a solo exhibition of American collagist and conceptual artist Barbara Kruger. And fellow American artist Cindy Sherman, known for her chameleonic self-portraiture, is the focus of a solo show at Hauser & Wirth Menorca, on the picturesque Balearic Islands.

Each of these artists — whether through sculpture, photography, video, painting or language — has challenged conventional portrayals of women’s bodies, emotions and experiences. And they’ve managed to sustain a legacy of radical, often political art, over the course of decades. (Almost all of these current exhibitions include new or recent bodies of work.) That their art remains in focus is both a notable feat and a sign of the times.

Asked what might be the reason behind such enduring interest, Gabriella Nugent, a London-based art historian and curator specializing in global modern and contemporary art, wrote over email: “The 1970s witnessed the emergence of second-wave feminism and a critique of the structures of patriarchy that determined women’s public and private lives.”

During this transformative period, feminist art historians such as Linda Nochlin and Ann Sutherland Harris helped to, as Nugent said, “rehabilitate the work of women artists and expose the terms of their exclusion” through groundbreaking texts and exhibitions. She explained that the likes of Kruger and Sherman “came of age against this backdrop and engaged with the debates of the time in their artwork.”

Bourgeois (who will also receive a major retrospective at PoMo in Trondheim, Norway, from February 2026) found a wider audience around the same time as this younger generation of artists, despite having practized art since the 1930s. “In the 1970s the women’s art movement in New York took her (Bourgeois) up as a key precursor to feminist art,” said Jo Applin, who helped curate both the drawing display and sculptural show both taking place at the Courtauld Gallery this summer.

The 1970s were a generative decade for pioneering art in other ways. It was a “watershed moment in terms of arts’ relationship to mass media,” explained Tanya Barson, curatorial senior director at Hauser & Wirth, who added that this transformation laid the foundation for artists like Sherman. “She became part of a group of artists called the ‘Pictures Generation’ who made work that examined this relationship. Her work is made for an audience who have grown up not just with film and advertising but with television as part of their reality. Looking back, it was the first generation for which this was the case,” Barson told CNN.

In many ways, Sherman was an artist ahead of her time. “Her use of photography to record these identities is something that prefigures the use of social media today,” Barson said of her performances and manipulation of personas. “She was really in advance of a transformation in society and our relationship to images, to media more widely, and our use of them,” added Barson.

“I think Sherman’s work expresses something fundamental about how we live today and how we relate to images. In many ways, we live through images now. We also are absolutely involved in constructing our identities for an ever present but invisible and anonymous audience,” Barson said. While Sherman constructed some of these personas 50 years ago, Barson believes they are perennially familiar. “We know these subjects, we have met them or seen them on TV, or on Instagram or Tik Tok,” she said.

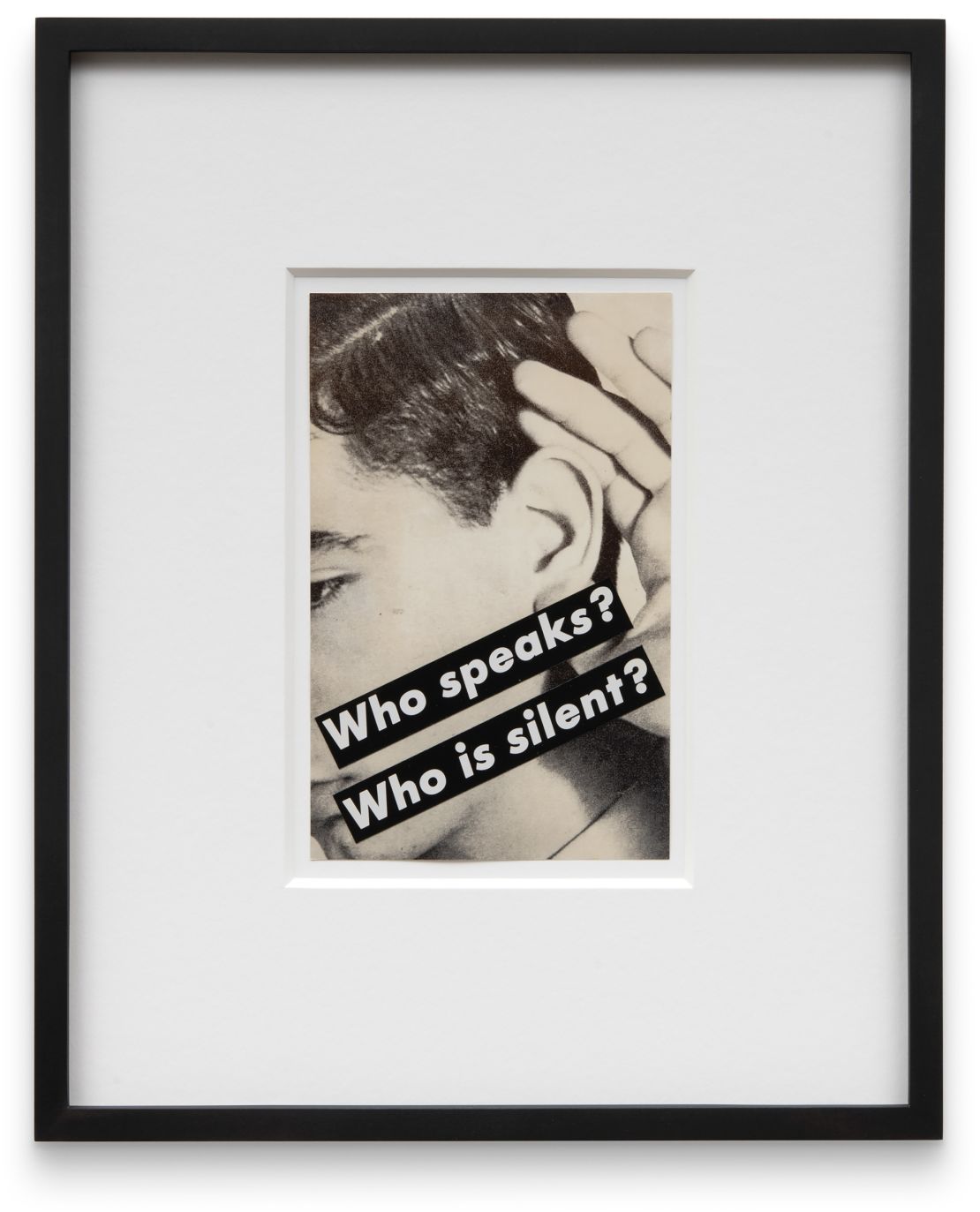

Kruger, another key figure of the Pictures Generation, began borrowing advertising and graphic design techniques to explore power in the context of consumerist and patriarchal structures. The artist continues to interrogate the interplay between image and text in culture today –– illustrating the persistent dominance of advertising, as well as the peculiarities of newer phenomena, such as memes.

The feminist movement that coincided with the emergence of these artists addressed issues around the emancipation of women, particularly reproductive rights and sexuality. Such issues have come back under the spotlight amid the rollback of legal rights regarding women’s bodily autonomy in some Western nations.

“Many of the debates that charged their work in the 1970s are still ongoing today, from abortion in the United States to child care in the United Kingdom,” explained Nugent. The slogan “Your body is a battleground”, used by Kruger in her famous poster for the 1989 Women’s March in Washington, D.C., resurfaced last year in another of her pieces displayed on the side of a truck in Miami, FL., as part of a travelling project calling for reproductive and healthcare access for all.

Nugent said that, although “women artists all over the world have long addressed the gender-defined differences that they had to navigate,” the symbolic impact of US President Donald Trump’s reelection and rise of self-proclaimed misogynist influencer Andrew Tate may partly explain why the work of these artists resonates today.

Newer audiences may find comfort in engaging with artists who have lived and worked through earlier eras of political struggle. At the same time, the potency of their art has enshrined many of these figures as perennially relevant, even beyond immediate political lines. For instance, Bourgeois’ deeply personal works “speak to universal themes of fear, anger, desire, anxiety that we can all identify with,” said Applin. It could be why her work, like that of Sherman, Kruger, and countless other female artists who made their names in the 20th century, continues to be relevant.