In late Ottoman Jerusalem, Jaffa and Haifa, Jewish intellectuals read Arabic fluently, translated medieval Islamic texts into Hebrew, argued about Arabic grammar, mapped the land, and treated Islamicate civilisation as shared cultural inheritance rather than a foreign object of study.

This world is not a footnote to the history of Palestine. It is the starting point of Hebrew Orientalism: Jewish Engagement with Arabo-Islamic Culture in Late Ottoman and British Palestine by Mostafa Hussein.

Hussein’s work is a meticulously researched and quietly unsettling study of how engagement with Arabo-Islamic culture shaped modern Hebrew culture and, ultimately, the Zionist project itself.

Hussein’s book does not ask whether Hebrew Orientalism was good or bad, emancipatory or oppressive, but instead, it asks how it worked.

That insistence on practice rather than posture is what gives the book its force.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on

Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

By tracing the daily intellectual labour of Jewish writers who studied Arabic, translated Islamic texts, catalogued Palestinian flora, and narrated the land through Arab sources, Hussein reconstructs a cultural world in which intimacy and domination were not opposites but coexisted, often uneasily, within the same bodies of knowledge.

Diversity within Jewish scholarship

The protagonists of this book are not the usual figures of colonial authority. They include Sephardi and Oriental Jews born in Palestine, alongside Ashkenazi immigrants who arrived from Eastern Europe and immersed themselves in the Arabic language and local culture.

Figures such as David Yellin, Abraham Shalom Yahuda, Isaac Yahuda and Eliyahu Sapir emerge not as marginal mediators but as central architects of Hebrew cultural production.

They read Arab geographers and botanists, translated Arabic literature, and insisted that knowledge of Arabic was indispensable to Jewish life in Palestine.

Arabs were positioned as pupils, relics of a glorious past, or obstacles to national fulfilment

For many of them, Arabic was “sefat ha-arets”, the language of the land, without which belonging could not be articulated.

Hussein’s achievement lies in refusing to sentimentalise this moment. Early Hebrew engagement with Arabo-Islamic culture was never innocent. It oscillated between admiration and hierarchy, closeness and distance. Jews and Arabs were imagined as Semitic kin, even as Arabs were positioned as pupils, relics of a glorious past, or obstacles to national fulfilment.

The book is particularly strong when it dwells in this ambivalence rather than seeking to resolve it.

An affection for the Arabic language and literature coexisted with a refusal to recognise contemporary Palestinian Arabs as political actors with legitimate claims to the land.

This tension becomes most vivid in Hussein’s sustained engagement with David Yellin.

Yellin was a committed Arabist who translated Arabic texts, championed Arabic education among Jews, and described himself as a lover of the Arab people.

Yet when Palestinian nationalists mobilised Arab history to assert political rights, Yellin rejected their claims, distinguishing between Arabs of the past and Arabs of the present.

The culture he admired belonged safely to medieval texts and frozen landscapes, not to living communities demanding sovereignty.

Hussein shows how this move was not a personal contradiction but a structural feature of Hebrew Orientalism itself.

The weaponisation of knowledge

As the book moves from the late Ottoman period into the British Mandate, the stakes sharpen. What had once been a shared cultural horizon increasingly became a resource for settler indigenisation.

Arabic and Islamic sources were mined to demonstrate ancient Jewish presence, to authenticate biblical geography, and to legitimise Jewish claims to the land.

Palestinian Arabs, meanwhile, were increasingly portrayed as late arrivals or custodians without history.

In the shadow of the live feed: Avi Shlaim’s ‘Genocide in Gaza’

Read More »

The same knowledge practices that once enabled coexistence were now redeployed to undermine the Palestinians’ indigenous claim.

This is where Hebrew Orientalism makes its most significant contribution. Rather than locating settler colonialism solely in institutions, policies or violence, Hussein traces it through philology, translation and scholarship.

Mapping, botany, folklore and literary history become sites of political struggle.

Hebrew writers catalogued Palestinian placenames in order to replace them. They studied Arab agricultural practices only to disparage them. They translated Arabic texts to enrich Hebrew while stripping those texts of their contemporary social and political meaning.

Hussein’s engagement with settler colonial theory is careful and persuasive.

Drawing on Patrick Wolfe’s formulation that settler colonialism is a structure rather than an event, the book shows how cultural knowledge functioned as a long-term instrument of replacement.

Land was not only seized through purchase or force but reimagined through text. Geography was rewritten, history reordered, and belonging recalibrated in ways that rendered Palestinian presence contingent and Jewish presence primordial.

Distinct from European orientalism

Crucially, the book refuses to collapse Hebrew Orientalism into a crude imitation of European colonial discourse.

Many of Hussein’s figures were themselves deeply entangled in the Orient. Sephardi and Oriental Jews did not experience Arabic and Islam as exotic objects but as lived environments.

Even Ashkenazi Arabists often approached Arabic culture not from a position of imperial confidence but from a place of cultural anxiety, searching for authenticity outside Europe.

What is the Nakba?

+ Show

– Hide

The Nakba is one of the key events in modern Middle East history and one that has come to define the Israeli-Palestinian conflict ever since.

Also known as “The Catastrophe”, it began in late 1947 and 1948, as the new state of Israel came into existence.

Palestine was part of the Ottoman Empire for hundreds of years until it was captured by the UK at the end of World War One (1914-18).

The League of Nations – a forerunner of the UN – gave Britain a “mandate” over Palestine after the war, which did not take into account the wishes of the native Palestinian population.

The aim of such mandates was to bring about “the rendering of administrative assistance and advice” to native populations until they were deemed capable of standing alone as independent states.

What was the problem?

The British Mandate incorporated the Balfour Declaration, sent by Arthur Balfour, the British foreign secretary, to Lord Walter Rothschild, a prominent member of the British Jewish community, in 1917.

It pledged to establish “in Palestine a national home for the Jewish people”, who made up less than 10 percent of the population at the time.

During the mandate years (1923-48), the UK facilitated the immigration of European Jews to Palestine, increasing their population 10-fold, from 60,000 in the pre-Mandate era to 700,000 by 1948.

They also trained, armed and supplied Zionist groups, and allowed them a degree of self-governance.

In contrast, the native Palestinian population, which rejected European Jewish immigration and called for independence, was violently suppressed.

The number of Jews arriving in Palestine from Europe and elsewhere increased in the wake of the Holocaust, which systemically targeted Jews and others, resulting in the deaths of more than 6m people.

In February 1947, Britain announced it would terminate the mandate and turn the question of Palestine over to the newly formed United Nations.

The UN adopted a partition plan in November 1947, which divided Palestine into two parts: 55 percent would form a Jewish state, while 45 percent would create an Arab state. Jerusalem would be kept under international control.

But many argue that the plan did not take into account populations at the time.

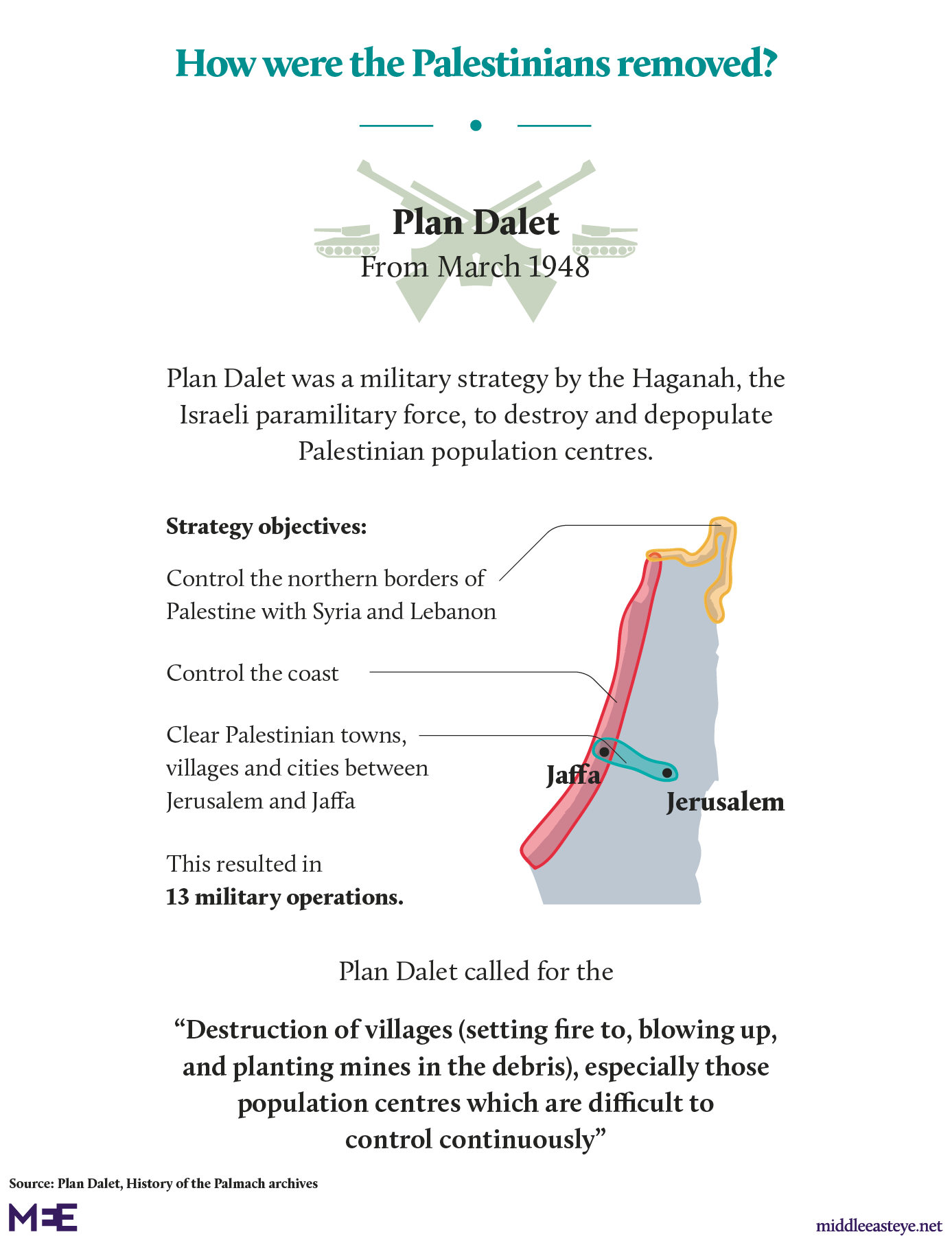

In addition, Jewish paramilitary groups produced a strategy to control the borders of the new territory, called Plan Dalet (below).

Some of their members would go on to become key Israeli leaders, including Yitzhak Rabin (prime minister 1992 – 1995), Ariel Sharon (prime minister 2001 – 2006) and Moshe Dayan (minister of defence 1967 – 1974).

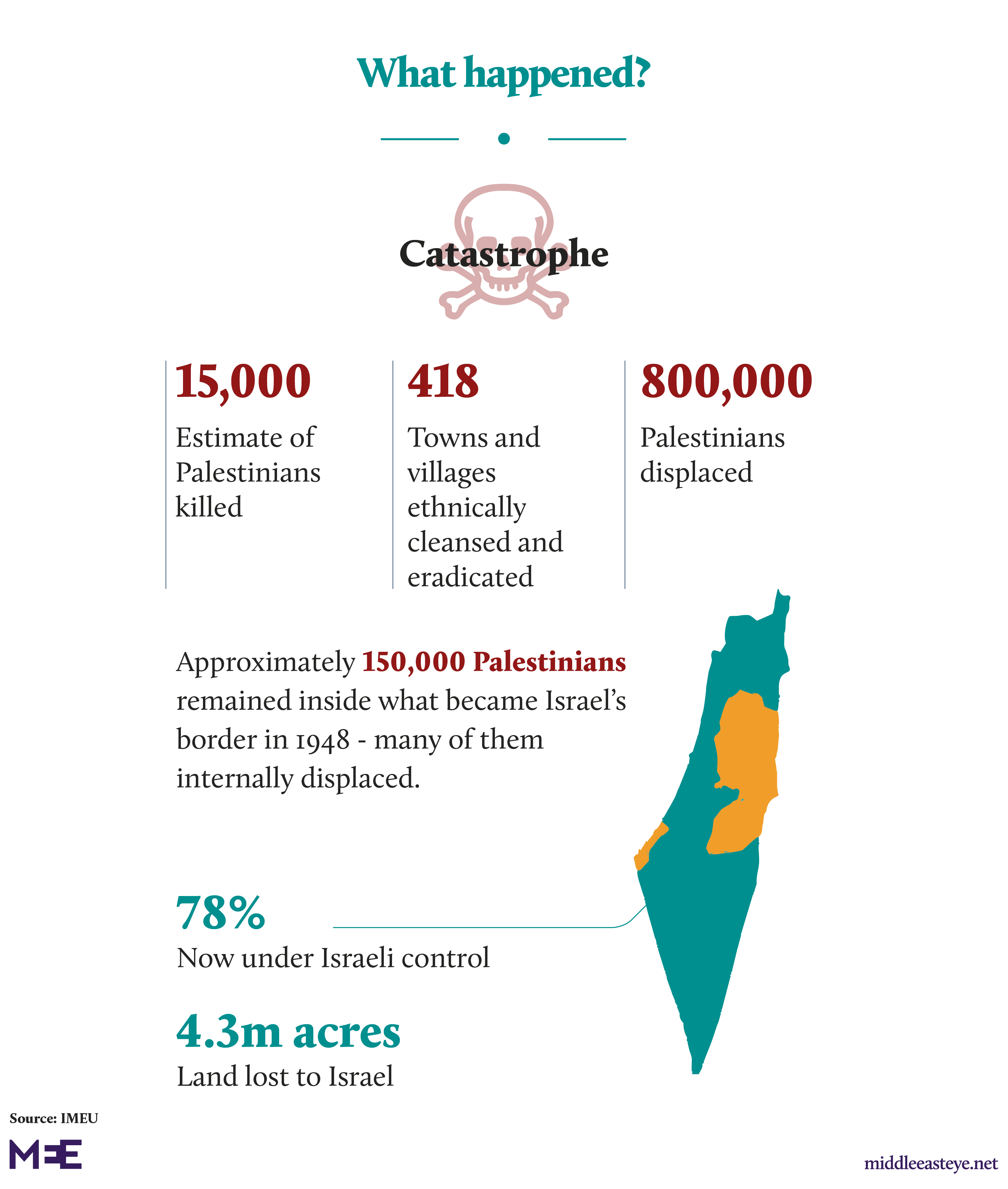

In the weeks and months that followed, thousands of Palestinians were killed or driven from their homes and communities uprooted by Jewish paramilitary groups.

Jews were also killed by Palestinian groups, if not in the same numbers.

On 14 May 1948, the State of Israel was unilaterally declared, a day before the British Mandate officially expired.

The new state had increased its share of historic Palestine from 55 percent to 78 percent. The remaining 22 percent was under Arab control.

Many of the Palestinians who fled or were driven from their homes never returned to historic Palestine. Much of it is now the modern-day state of Israel.

More than 70 years later, millions of their descendants live in dozens of refugee camps in Gaza, the West Bank, and surrounding countries, including Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon.

Many still keep the keys to the homes that they and their families were forced to leave.

Nakba Day is now a key commemorative date in the Palestinian calendar. It is traditionally marked on 15 May, the date after Israeli independence was proclaimed in 1948.

Some Palestinians also observe it on the day of Israeli independence celebrations, which itself changes from year to year due to variations in the Hebrew calendar.

This hybridity complicates easy moral binaries without diluting responsibility. Hebrew Orientalism was neither purely celebratory nor simply oppressive: it was productive, generative, and politically consequential.

One of the book’s quiet strengths is its demonstration that modern Hebrew culture did not emerge in isolation. Hebrew was revived through Arabic. Zionist visions of the land were shaped by Arab geographies.

Jewish claims to indigenousness were articulated using Islamicate historical frameworks. This is not a minor corrective to existing scholarship; it is a reorientation of how cultural production in Palestine must be understood.

Future areas of exploration

The book also resonates beyond its historical frame. Without polemicising, Hussein suggests that the early Zionist aspiration to become native to the land has been hollowed out by the persistence of dispossession and expansion.

The tragedy is not only that coexistence failed, but that the intellectual tools that once made it conceivable were transformed into mechanisms of exclusion. Culture did not merely accompany politics. It prepared the ground for it.

There are, inevitably, questions the book leaves open. Palestinian Arab intellectual responses appear largely through moments of contestation and protest.

Nakba: Britain and the secret 1948 Palestine memos

Read More »

Future research could build on Hussein’s work by reconstructing Arab engagements with Hebrew Orientalism as a field in its own right.

How did Palestinian scholars read Hebrew translations of Arabic texts? How did they respond to the Hebraisation of geography and history? What parallel knowledge practices emerged in resistance to these transformations?

Similarly, Hussein’s focus on elite intellectuals raises questions about reception. How were these Hebrew texts read by ordinary settlers? How did popular culture absorb or resist Orientalist frameworks? And what happened to these knowledge practices after 1948, when the landscape they helped to reimagine was violently remade?

These are not shortcomings but invitations. Hebrew Orientalism opens a field rather than exhausting it.

It is a book that insists on taking culture seriously, not as ornament or afterthought, but as a terrain where power is assembled, justified and naturalised.

Hussein has written a work that is rigorous without being arid, critical without grandstanding, and attentive to the tragic ironies of history without indulging in nostalgia.

It forces the reader to confront an uncomfortable truth: that intimacy can be instrumental, that learning can dispossess, and that love for a culture does not preclude the erasure of its people.

Hebrew Orientalism: Jewish Engagement with Arabo-Islamic Culture in Late Ottoman and British Palestine is published by Princeton University Press