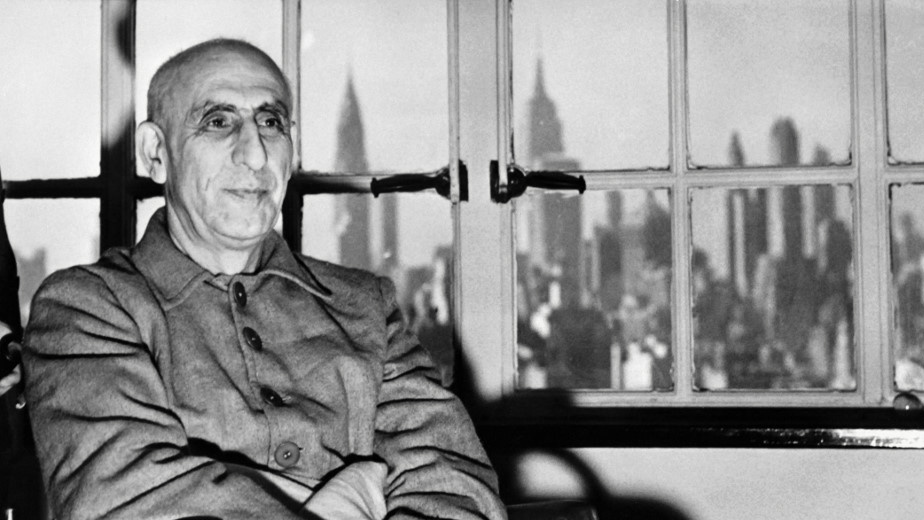

“We will not be coerced, whether by foreign governments or by international authorities,” former Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh warned the UN Security Council in 1951.

More than seven decades later, as a US carrier strike group enters the Indian Ocean and guided-missile destroyers fan out across the Middle East, Mosaddegh’s warning feels less like history and more like live commentary.

Warships do not drift into position by accident. Their movement signals intent. Similarly, “intelligence dossiers” are typically not compiled to uncover truth, but concocted to manufacture consent for military action – the scaffolding of an intervention already set in motion.

It is in this context that Israel has handed US President Donald Trump what it calls decisive evidence that Iranian authorities executed hundreds of detained protesters during the recent nationwide crackdown. That Tel Aviv should now present itself as the authoritative provider of evidence against Iran would be comical, were the stakes not so grave.

The state that has lobbied relentlessly for war with Tehran, that openly declares regime change in Iran to be a strategic objective, and that stands to gain more than any other actor from Iranian collapse, is suddenly cast as a neutral humanitarian witness. Tel Aviv has thus been elevated to chief prosecutor; its claims treated not as advocacy, but as fact.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on

Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

This does not mean Iran is not in crisis. It is. Large numbers of Iranians have been driven into the streets by genuine exhaustion after decades of economic strangulation. Their grievances are real, their rage undeniable.

But such moments are also those in which popular movements are most vulnerable, not only to repression, but to capture. External powers need not invent domestic discontent; they need only steer it.

Familiar structure

The pattern is well established. There was the 1964 coup in Brazil against leader Joao Goulart; the 1973 coup in Chile against Salvador Allende; and before those, the Congo coup in 1961, where Patrice Lumumba was removed and killed. Then there’s the long, murky story of counter-revolutionary reversals following the Arab Spring.

These cases are not identical, but the structure is familiar enough to serve as a warning.

Since the Second World War, when movements threaten entrenched western interests, sanctions follow. Economic crises are engineered. Internal divisions are inflamed. Media campaigns multiply. Counter-revolutions are funded.

If these measures fail, coups are organised, occupations launched, or wars justified in the language of salvation.

That episode did not merely alter Iran’s political trajectory; it defined the playbook. The same tools are visible today

Iran knows this pattern not as theory, but as lived trauma. In 1953, Mohammad Mosaddegh, a democratically elected prime minister, was overthrown in a US-British coup not because he ruled brutally, but because he nationalised Iran’s oil. At the time, the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, which later became known as BP, offered Iran only 16 percent of net profits from its own resources.

Britain responded with a blockade, shutting down the Abadan refinery, pressuring foreign buyers to refuse Iranian oil, and deliberately plunging the economy into crisis.

When economic warfare proved insufficient, London persuaded Washington to intervene by invoking Cold War fears. The CIA’s Operation Ajax flooded Iran with disinformation, bribed politicians, harassed religious figures, and orchestrated unrest. Mosaddegh was removed. The shah was restored. Even the CIA now officially acknowledges the coup as undemocratic.

That episode did not merely alter Iran’s political trajectory; it defined the playbook. The same tools are visible today. Reports of attacks on dozens of mosques across Iran raise unavoidable questions about external efforts to stir division and internal infighting, through precisely the same fault lines exploited seven decades ago.

Nor is this merely a matter of covert destabilisation. Israeli media figures have spoken openly of what would follow regime collapse, declaring that once Iran falls, it will be bombarded across its territory in the same manner as Syria was systematically stripped of military capacity after the ousting of President Bashar al-Assad.

The message is unambiguous: regime change is not the end goal, but the precondition for comprehensive dismantling.

Slow siege

Since 1979, Iran has endured one of the longest and most comprehensive sanctions regimes in modern history. What began with asset freezes and oil bans evolved into a system targeting finance, energy, trade, technology and daily life.

Sanctions intensified through the 1990s, expanded multilaterally after 2006, were partially lifted under the 2015 nuclear agreement, and then were fully reimposed under Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign in 2018.

Last year, European powers triggered the snapback mechanism, automatically restoring UN sanctions under the banner of non-compliance and human rights.

Iran protests: Are viral atrocity numbers part of a march to war?

Read More »

Sanctions are often described as a peaceful alternative to war. In reality, they function as a slow siege. They collapse currencies, hollow out societies, radicalise politics, and ensure that ordinary people pay the price for geopolitical confrontation.

Britain used this method against Iran in 1951. The US has refined it ever since. It is no coincidence that calls for regime change so often accompany demands for harsher sanctions; those advocating them understand exactly who absorbs the pain.

Washington’s interest in Iran is rooted in hegemony. Iran’s oil is not merely an economic asset; it is a strategic lever in the global contest with China.

Today, China is the primary buyer of Iranian crude. Weakening Iran therefore weakens a critical energy artery for Beijing: Iran accounted for roughly 13 percent of China’s seaborne oil imports in 2025, with around 1.38 million barrels per day heading to Chinese buyers.

Israel’s agenda goes further. Over the past two years, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has repeatedly addressed the Iranian people directly, urging them to take to the streets, framing Israeli military actions as clearing the path to freedom, and promising assistance once the regime falls.

Former Defence Minister Yoav Gallant was even more explicit, speaking of steering events “with an invisible hand” – stressing the centrality of mass action while remaining formally in the background.

‘We are with you’

This rhetoric has increasingly been matched by media signalling. Israeli outlets have openly suggested that foreign actors are arming protesters, a claim voiced most bluntly by a diplomatic correspondent on Channel 14 – the television network closest to Netanyahu – who gloated that protesters were being supplied with live firearms, “which is the reason for the hundreds of regime personnel killed. Everyone is free to guess who is behind it,” he added.

Such remarks are not marginal slips, but part of a broader Israeli media ecosystem that has begun to say aloud what was previously left implicit.

These media cues sit uneasily alongside official intelligence messaging. Following the war last June, Mossad director David Barnea issued a rare and striking declaration, assuring both his agency and the public that Israel would continue to “be there, like we have been there” – language widely read as foreshadowing sustained covert activity inside Iran.

And last month, a Persian-language X (formerly Twitter) account that has been linked to the Mossad urged Iranians to take part in protests, declaring: “Go out together into the streets. The time has come. We are with you. Not only from a distance and verbally. We are with you in the field.”

While Israeli officials have formally denied any connection to the account, intelligence agencies have long relied on deniable fronts precisely for such purposes.

Nor is this limited to covert signalling. Israeli flags have become a conspicuous feature of anti-regime demonstrations outside Iran, accompanied by a coordinated social-media campaign amplifying specific narratives and preferred political outcomes.

An Al Jazeera data analysis showed how Israel-linked accounts worked systematically to shape global perceptions of the protests, promoting Reza Pahlavi, the son of Iran’s last shah, as the singular political alternative. Pahlavi himself engaged with the campaign, a move that was swiftly magnified by Israeli accounts portraying him as the “face of the alternative Iran”.

These interventions are not isolated. They align with a broader strategic vision increasingly articulated in Israeli political and intellectual circles: the weakening and eventual fragmentation of Iran.

Israeli editorials and policy papers have argued openly for partitioning Iran and encouraging ethnic secession, while others have advocated arming minorities to destabilise the state from within. This is not fringe speculation; it appears in mainstream outlets and policy debate.

Colonial choreography

The promotion of Reza Pahlavi as Iran’s “alternative” must be understood in this context. While claiming to defend Iran’s territorial integrity, he has called for US military strikes on his own country, and supported intensified sanctions that have devastated Iranian society.

His path mirrors that of his father with almost ritual precision: Mohammad Reza Shah was first installed in power in 1941 by the British and the Soviet Union after they forced his father to abdicate, then reinstalled in 1953 after the CIA-MI6 coup against Mosaddegh.

Today, the son seeks installation yet again, this time by the US and Israel, repeating the same colonial choreography under a different flag. He would rule, as his father did, through external sponsorship rather than internal legitimacy.

His father governed through Savak, a security apparatus created with CIA and Mossad assistance, and infamous for torture and repression. One of Savak’s senior figures, who spent decades in hiding in the US, now faces major civil litigation there over the police force’s past atrocities.

None of this absolves Iran’s authorities of responsibility for repression or violence. But it exposes the emptiness of foreign moral posturing

The past is not merely remembered; it is being rehearsed.

None of this absolves Iran’s authorities of responsibility for repression or violence. But it exposes the emptiness of foreign moral posturing.

Those who have starved Iran economically for nearly half a century, backed a devastating proxy war in the 1980s, and now openly discuss partition – while their own hands are stained with contemporary regional crimes – are the least credible custodians of Iranian freedom.

There is nothing accidental about the timing of the present escalation. 1 February marks the anniversary of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s return to Tehran in 1979, the day a foreign-installed monarchy finally collapsed and Iran reclaimed its political independence.

That preparations for a new American assault are now gathering pace around this date is not coincidence, but continuity.

It exposes a truth that has remained unchanged for more than seven decades: what Iran asserted in the early 1950s, and again in 1979 – sovereignty, independence and the right to self-determination – is precisely what external powers have never accepted, never forgiven, and never ceased trying to reverse.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.