In 1991, my parents took me to the movies for only the second time in my life. I was eight years old and already oversaturated with Egyptian cinema, thanks to countless unguarded hours spent in front of our television.

The film was Kit Kat, the highest-grossing comedy of that year, starring Mahmoud Abdel Aziz, one of Egypt’s biggest film stars of the 1990s.

Kit Kat was not the kind of family-friendly picture one would expect an eight-year-old to enjoy, let alone comprehend.

Adapted from the 1983 novel The Heron by Ibrahim Aslan, often dubbed the Egyptian Chekhov, the film revolves around Sheikh Husni (Abdel Aziz), an unruly blind man living in the working-class neighbourhood of Imbaba, who stubbornly refuses to accept his visual impediment.

The film is laced with sexual and existential themes, animated by a subtle but unmistakable political subtext.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on

Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

My innocent eight-year-old self grasped none of this, but it was undeniably funny, riotously, so.

Sheikh Husni’s deliciously irresponsible antics turned him into one of the most beloved heroes of 1990s Arab cinema.

Kit Kat was the first Egyptian film I saw in a cinema, and it was the reason I fell in love with Egyptian cinema at a time when Hollywood’s dominance was sweeping the region.

Years later, I would learn that the film was directed by Daoud Abdel Sayed, a filmmaker who became Egypt’s most beloved and influential auteur by the turn of the millenium.

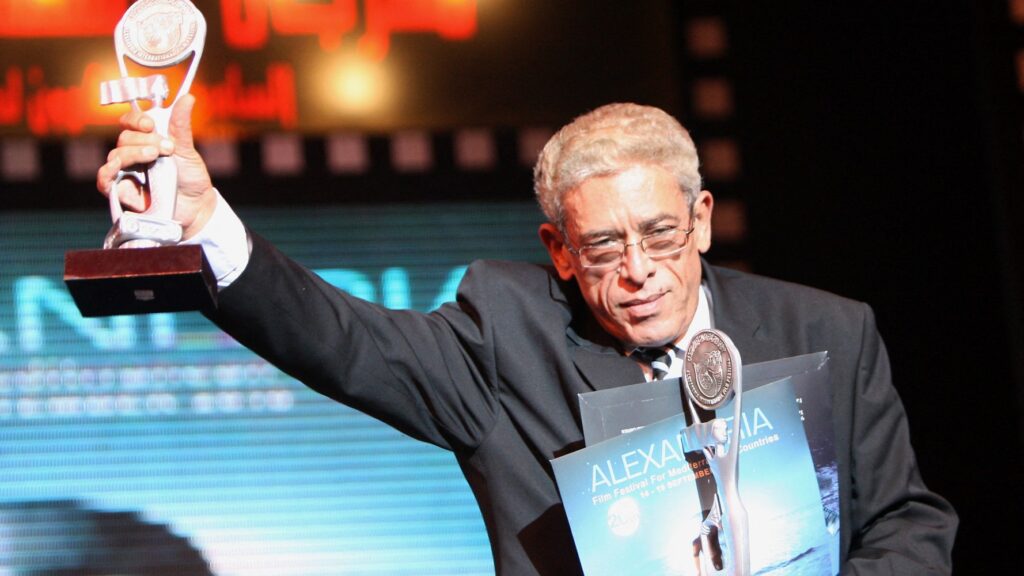

Abdel Sayed passed away on 27 December.

Social media and the Arab press were flooded with tributes to one of the most soulful filmmakers Egyptian cinema has ever produced.

International outlets, by contrast, barely noted his death.

Egyptian realism in the 1980s

Unlike his mentor, the great Youssef Chahine, Abdel Sayed’s films rarely travelled beyond the Arab world, despite acclaim at home.

His later opposition to the Sisi regime would add one last twist to a career spanning 40 years.

Born in Cairo in 1946 to a middle-class Coptic Christian family, Abdel Sayed studied film at the Higher Institute of Cinema, the only film school in Egypt at the time.

The President’s Cake is our favourite movie of 2025. Here are 11 other standouts

Read More »

He graduated in 1967, the year of the Six-Day War, when Israel occupied the Sinai Peninsula, effectively bringing Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Arab nationalist project to an end.

Abdel Sayed cut his teeth in the film industry as an assistant director to two of Egypt’s greatest filmmakers: Kamal El Sheikh on The Man Who Lost His Shadow (1968) and Chahine on The Land (1970).

Between 1976 and the early 1980s, he directed a series of remarkable short films that explored art and education against a backdrop of cultural decline.

He made his feature debut in 1985 with El-Sa‘alik (The Tramps), a rags-to-riches melodrama about two hustlers (Mahmoud Abdel Aziz and Nour El-Sherif) who achieve social mobility by entering the illegal drug trade.

The film is deeply rooted in 1980s realism, a movement that sought to document the radical social transformations triggered by Anwar Sadat’s Infitah (“Open Door”) – the economic liberalisation programme that shifted Egypt overnight from socialism to capitalism.

It brought out the erosion of the middle class, the rise of an empowered nouveau riche, and the retreat of collectivist values in the face of market-driven individualism.

All are themes that informed not only The Tramps but much of 1980s Egyptian cinema.

Looking for Sayyid Marzouk

While The Tramps may initially appear cut from the same cloth as works by Egyptian auteurs Atef el-Tayeb, Mohamed Khan, and Khairy Beshara, it diverges in one crucial respect: it contains none of the defeatism or self-pity that marked many of its contemporaries.

The threat posed by unchecked capitalism to a vanishing middle class would inform much of Abdel Sayed’s work, but his narratives were more layered, and his imagery more dreamlike, than the austere realism of the period.

Money, across Abdel Sayed’s cinema, emerges as the ultimate corrupting force – an invasive agent rendered all the more destructive by Sadat’s relentless neoliberal turn.

Money, across Abdel Sayed’s cinema, emerges as the ultimate corrupting force

Abdel Sayed’s sophomore feature, Al-Baḥth ‘an Sayyid Marzouk (Looking for Sayyid Marzouk, 1991), marked his first true masterpiece.

Nour el-Sherif plays Youssef, a directionless middle-class bureaucrat who crosses paths with the titular enigmatic millionaire before becoming implicated in a murder.

Unfolding over the course of 24 hours, the film operates both as a critique of the unchecked power of the new aristocracy and as an existential meditation on the futility of the search for meaning.

It is an intoxicating nocturnal odyssey through Cairo, a Garcia Marquez–like carnivalism populated by oddballs adrift in moral chaos.

The movie introduced two of Abdel Sayed’s signature elements: a gravitation towards high concepts; a knack for working with major stars; and a tendency to infuse his socio-political subjects with larger philosophical inquiries that set him apart from his contemporaries.

Recurring themes also crystallise here: an ambiguous relationship with an indifferent God; a faith in the redemptive power of love; and a depiction of sexuality as a means of self-actualisation.

Kit Kat and Land of Dreams

Neither The Tramps nor Sayyid Marzouk prepared audiences for Kit Kat, a lightning bolt that electrified the collapsing Egyptian cinema of the time.

The film follows the misadventures of Sheikh Husni, a blind man addicted to hashish, women, and life itself.

His son, Youssef (Sherif Mounir), dreams of escaping Imbaba for Europe, fleeing a neighbourhood slowly decaying under economic stagnation.

Knowing the limits: Bassem Youssef makes a ‘safe’ return to Egyptian TV screens

Read More »

Here, Abdel Sayed achieved, perhaps for the first time, a perfect equilibrium between uncompromising artistry and mass entertainment, enlivening a loose narrative with some of the most inventive comic set pieces of 1990s Arab cinema.

Beneath the film’s manic humour lies a deep reservoir of despair.

Kit Kat is a vivid portrait of a marginalised community whose fragile social fabric is torn apart by the same capitalist forces that haunt Sayyid Marzouk and Abdel Sayed’s later films.

Imbaba becomes a space of thwarted desires and aborted dreams, a microcosm of Mubarak’s Egypt: a nation drifting aimlessly under inert leadership.

Kit Kat would remain the highest-grossing film of Abdel Sayed’s career, cementing his status as one of Egypt’s most popular filmmakers throughout the 1990s and early 2000s.

He followed it with Ard Al-Ahlam (The Land of Dreams), a bittersweet comedy and his sole collaboration with Faten Hamama, the Arab world’s greatest actress.

Hamama plays Narges, a middle-class widow who embarks on a nocturnal quest to recover her lost passport and catch a flight to the United States.

Set on New Year’s Eve, The Land of Dreams serves as a gentler companion piece to Sayyid Marzouk.

In her final screen performance, Hamama embodies a segment of Egypt’s aging middle class, particularly Coptic Christians, torn between the promise of emigration and the diminishing comforts of home.

Magical realism once again shapes both the film’s aesthetics and its themes.

Unlike the ominous Cairo of Sayyid Marzouk, the city becomes a phantasmagorical playground, closer to the Paris of French filmmaker Jacques Rivette, where our heroine rediscovers herself.

Sarek al-Farah (The Joy Thief, 1995) returned to the slum world of Kit Kat with a story about a handkerchief seller racing against time to secure a dowry before his lover is married off.

A subtle meditation on time as an adversary of the poor and the limited avenues for happiness conceived as a folktale seeping with wit and warmth, The Joy Thief remains Abdel Sayed’s most underrated film.

Later films

Abdel Sayed inaugurated the new century with Ard al-Khof (The Land of Fear, 2000), a film that ranks as his second masterwork.

In arguably his finest screen performance, the late Ahmed Zaki, Egypt’s most acclaimed film star, plays Yehia, an undercover detective forced to abandon normal life and become a drug lord in order to uncover the country’s elaborate drug network.

Set in the 1960s, The Land of Fear is Abdel Sayed’s richest, most philosophically probing work. A crime saga and existential allegory about the slipperiness of identity, the thin line between good and evil, and God’s silence in the face of it all.

Yehia represents Adam, the fallen man who finds himself alone in a foreboding world, abandoned and discarded by his maker.

On a political level, The Land of Fear mirrors the collapse of the Nasserist delusion: the end of the protective state and the abandonment of its loyal servants to the wilderness of capitalism.

Bereft of purpose, the new Egyptian individual, Abdel Sayed suggests, is compelled to confront a new reality; one that demands a new identity, a new sense of meaning, and a new moral framework.

Mowaten we Mokhber we Haramy (A Citizen, a Detective, and a Thief), which followed a year later, stands as Abdel Sayed’s most perfect distillation of post-Nasser Egypt.

Khaled Abol Naga plays Selim, an aspiring novelist and former political activist now leading a hedonistic existence.

His life spirals out of control when the titular thief, Margoushy (played by shaabi singer Shaaban Abdel Rahim, a major sensation at the time), accidentally breaks into his home and steals the manuscript of his novel.

In an attempt to retrieve it, Selim turns to Fathi, a low-ranking police officer who had once been assigned to spy on him during his activist days.

Abdel Sayed offers a remarkably subtle, clear-eyed study of a society changing beyond recognition.

The intelligentsia has grown decadent, compromising its ethos in order to adapt to the new Egypt.

Its resilient nouveau riche, by contrast, has succeeded in moulding the nation in its own image, embedding it with conservative values.

In this new Egypt, the only constant is the role of authority: still watchful, still unyielding and controlling, but now economically unshackled.

The bond the three forge is born purely of convenience; a discordant vision of a nation drowning in chaos and senselessness.

The musical number at the end is both a celebration of the country’s capacity for survival and an admission of its incurable disfigurement.

Response to Sisi

After a nine-year hiatus, Abdel Sayed returned with Rasayel el-Bahr (Messages from the Sea, 2010), released a year before the 2011 revolution.

Asser Yassin plays Yehia, a stammering medical school dropout turned fisherman who leads an isolated life in his family’s old summerhouse in Alexandria and begins a stormy affair with a cryptic woman (Basma) who may or may not be a sex worker.

Messages from the Sea stands as Abdel Sayed’s final testament to Mubarak’s Egypt.

His Alexandria is a fallen metropolis – a decaying city hollowed out by gentrification and the constricting mores of the country’s new ruling class.

In this 21st-century incarnation of the city, individual privacy is scarce, desire is forbidden, and difference is punished.

Abdel Sayed’s final film, the supernatural drama Qudrat Ghayr Adiya (Out of the Ordinary, 2014), arrived four years later in a radically transformed Egypt.

The 2011 revolution had failed; the Muslim Brotherhood’s ill-fated rule drove many intellectuals to back Sisi and the military coup; and a new republic set about implementing voracious neoliberal policies that would dwarf Sadat’s Infitah in both their extremity and their disdain for the poor.

Abdel Sayed initially backed Sisi, stating in an interview that “he’s the only who could fill in the position of the president”.

He would later become disillusioned with his rule, and in 2018 announced his boycott of the presidential elections, a decision that led to a lawsuit accusing him of “inciting the overthrow of the regime”.

In subsequent interviews, he took further jabs at the regime, stating in 2019 that “the Egyptian state treats cinema as a means of serving the regime.”

For me and for many of my generation, who grew up idolising Abdel Sayed as both visionary artist, entertainer, and defiant role model, parts of ourselves have died with him

In 2022, he announced his retirement, justifying the decision by arguing that his brand of socially conscious, mass-oriented cinema no longer had a place in an industry that had pivoted toward frothy, mind-numbing entertainment for the wealthy.

I met Abdel Sayed briefly, shortly after the release of Messages from the Sea in 2010.

He was soft-spoken, generous, and astonishingly humble. I was still a novice critic then, known only to English readers in Egypt, yet he treated me with seriousness and generosity during our long conversation on a memorable night in Cairo’s Garden City.

When he learned that I, too, lived in Heliopolis – another crumbling middle-class enclave – he insisted on driving me home.

That night, we spoke of his love for his audience, his quiet disappointment at the lack of international recognition, and the legacy he hoped to leave for his son.

I never saw him again. My professional exile from Egypt in 2015 erected a psychological barrier between me and many of the country’s intellectuals, whose early support for Sisi I could not reconcile with.

For me and for many of my generation, who grew up idolising Abdel Sayed as both visionary artist, supreme entertainer, and defiant role model, parts of ourselves have died with him: the innocent, idealistic, fervent younger selves who believed in the power of Egyptian cinema to provoke, to challenge, to illuminate.

We do not merely mourn a man we admired; we do not only grieve the sheltering solace he provided. We mourn who we once were. We mourn the Egypt we dreamed of – the Egypt we never brought, and may never, bring into being.