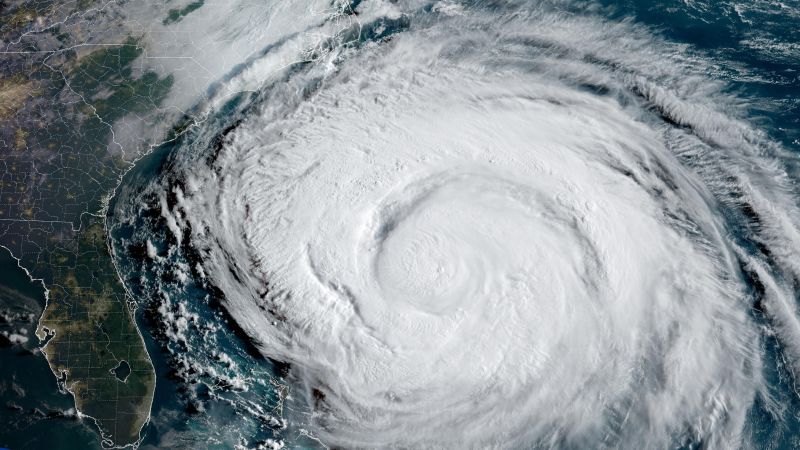

When a hurricane barrels across the ocean, it doesn’t just kick up waves, it stirs the water beneath it like a blender. That mixing drags cooler water from the deep ocean up to the surface in a process called upwelling.

Normally, that leaves behind a trail of chillier water that acts like natural storm repellent. Hurricanes need warm water to grow, so the cooler wake usually makes it harder for the next system to strengthen.

But Erin’s churning hasn’t put much of a dent in development potential for the storms trailing behind it: Two areas in the Atlantic have a medium chance to develop into at least tropical depression, according to the National Hurricane Center.

It’s because the Atlantic sea surface temperatures in much of Erin’s former track are still running above average. Climate change driven by fossil fuel pollution has warmed not just the surface, but the water below it. So when Erin drags up cooler water, it’s still plenty warm enough to fuel more storms.

In the past, one big hurricane could cool the ocean enough to slam the brakes on the next. Now, in an overheated Atlantic, that buffer is disappearing.