Scott Janssen’s heart was racing. He took shallow breaths. He couldn’t believe what he was seeing, but he tried to hide his shock.

It was a crisp autumn day, and Janssen was visiting Buddy, an elderly client, at his small brick home on a dead-end street in Durham, North Carolina.

Buddy had just lost May, his wife of 40 years. She was bed-ridden and had suffered from Alzheimer’s disease. Janssen, a hospice social worker, had been visiting the couple for nine months. During that time he had never heard May utter a sound and only saw her open her eyes once.

He also was worried about Buddy. The man was his wife’s sole caregiver; the couple never had children. He had spoon-fed, bathed and dressed May for years, with no help. At times, he’d open their bedroom window so his wife could smell the flowers in the garden he planted outside for her. He often talked to her while he worked in the garden, recounting stories of their life together.

As Janssen sat down, he noticed that Buddy’s depression had lifted. Janssen wondered why and probed for an answer.

“She was talking to the angels,” Buddy said. “In the last hour, God let me know.”

Buddy’s reference to God didn’t surprise Janssen. Buddy was a religious man who read the Bible and attended church.

But then Buddy asked Janssen an unexpected question.

“Want to see?”

Buddy walked into another room and returned with photos of his wife. He said he took them just before she died. Janssen was puzzled when he looked at the first photo of May. He saw her do something that seemed impossible. As he flipped through more photos of May’s last moments, his confusion turned to astonishment.

He then asked himself:

What the hell is going on?

Floating toward a bright light at the end of the tunnel. A sudden feeling of bliss. A reunion with long-lost loved ones. These are the hallmarks of near-death experiences. People who survive such moments often describe them as spiritually transformative, something that inspires belief in God and the afterlife.

But what Janssen saw in those photos was another type of purported communication between the living and the dead. They are called deathbed visions, or “end-of-life visions.” A deathbed vision is an experience in which a dying person, while awake, interacts with mysterious visitors, deceased relatives or spiritual figures. A person nearing death may ask cryptic questions like, “Who were those nice people who visited me last night?” — when there is no record of any hospital visitation.

For many terminally ill people, these deathbed visitations are messages from God. They reduce the fear of death and offer assurances that they won’t be alone when they depart.

But these end-of-life visions don’t just comfort the dying. They also can also inspire a spiritual transformation in those people who care for them.

When Janssen became a hospice social worker 33 years ago, he was an atheist. He didn’t talk about spiritual beliefs with his patients. When they asked for prayer, he demurred and changed the subject.

He also didn’t believe in deathbed visitations.

“I assumed it was a bunch of bulls**t,” he said. “I knew about deathbed visitations, but I thought it was disease-related hallucinations, deprivation of oxygen — it must be the morphine.”

And he certainly didn’t believe in God. Janssen was an existentialist who believed that a person, not a god, must provide answers to life’s big questions.

“I didn’t have a spiritual bone in my body,” he said. “I believed life had no inherent meaning. There was no soul, no overarching moral or spiritual order, no afterlife or reward for a life well lived.”

But today Janssen has become an unlikely ambassador for deathbed visions and similar experiences. He’s published articles on the subject, appeared on podcasts and written several books including “Light Keepers,” a novel that draws on his history with unusual end-of-life experiences.

Janssen has joined the vast majority of Americans who, according to a recent Pew Research Center poll, say they believe in the existence of human souls, the afterlife and “something spiritual beyond the natural world.”

What changed him?

Janssen said it took more than one photo. It was the culmination of “hundreds” of unusual encounters he had over the years with patients and through hearing first-person accounts. One began when a combat veteran asked him, “Do you believe in ghosts?”

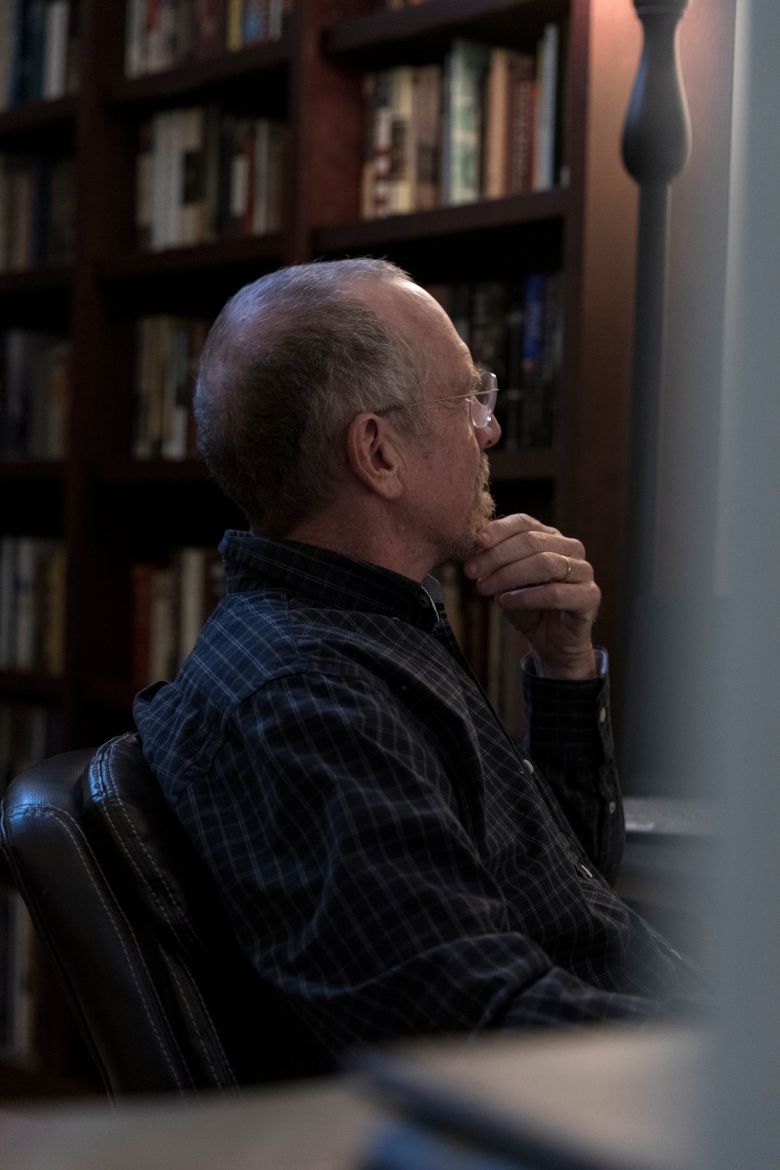

A slim man with a raspy voice and a salt-and-ginger goatee, Janssen lives in a tidy, three-bedroom house in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, with his wife, Sarah, a psychotherapist. Their home seems designed to promote tranquility with its uncluttered rooms, comfy furniture and a wood-burning stove in the living room near a miniature statute of the Buddha.

The average hospice nurse’s career lasts five years, according to Hadley Vlahos, a hospice nurse, in her recent best-selling memoir, “The In-Between.” Jannsen has been working in hospice care for 33 years. At 62, he currently works for a large healthcare center in North Carolina that dispatches him to far-flung places around the state. His silver 2025 Toyota Corolla already has 15,000 miles on it.

He said his job reveals what’s ultimately important in life.

“I often ask people how they want to spend what time is left,” he said. “No one ever says, ‘I just want to live long enough to see this bill passed or senate seat flipped.’ More often people say, ‘I just want to hold my mother’s hand. I want to hear my grandchildren playing in the next room.’”

But one patient asked him a question that he had no answer for.

His name was Evan (Janssen uses pseudonyms for his former patients and family members). Evan was in his early 90s and had been struggling with colorectal cancer for four years. He had long-standing depression from his time serving in a World II combat hospital. He had been praying for death.

On one of his visits, Janssen noticed that Evan’s gloom seemed lifted. He asked why, and Evan told him a war story.

Evan said he was part of a battle during WWII that resulted in a flood of casualties. The wounded arrived by train, and he spent much of that bitterly cold day transporting blood-soaked men on stretchers to a field hospital. During one such trip, Evan said he was exhausted and his grip slipped. The soldier on his stretcher tumbled to the ground, steam rising from his intestines as they oozed out. The soldier died in front of Evan.

“Later that night I was on my cot crying, “Evan told Janssen. “Couldn’t stop crying about the poor guy, and all the others I’d seen die.”

Evan then looked up. He said he saw a soldier sitting at the end of his cot. The soldier was wreathed in light and wordlessly conveyed to him that no matter how cruel the world looked, “We are all loved and connected,” Evan said.

Evan said the soldier visited him several more times but stopped after the war ended.

But now, more than four decades later, he was back.

Evans told Janssen that the man had sat at his bed the night before, and this time he talked. “He told me he was here with me, “Evan said. “He’s going to help me over the hill when it’s time to go.”

Evan died shortly after telling that story, Janssen said.

These stories didn’t initially inspire Janssen. They annoyed him.

He became a hospice worker to make this world better, not to ponder what came after. Janssen grew up in an upper-middle-class Irish Catholic family with an interest in social justice issues. When he was a teenager, he spent a couple of years at an all-White private school before insisting that his parents transfer him to a racially integrated public school.

He earned a master’s degree in American history and social work, working in a homeless shelter, with juvenile offenders and in a literacy program before choosing hospice work. He saw his work as a way to serve people who had been marginalized.

But he saw much of religion as an instrument of fear and social control. He could see it in some of his patients. They were terrified of a God of vengeance. Some saw their terminal illnesses as divine punishment and feared being cast into hell.

“I’d hear people talk about spiritual ‘surrender,’ and back then my knee-jerk response was, ‘Hell no. You surrender, not me,’” Janssen said.

Tom Beason, a hospice chaplain who worked with Janssen in the early 1990s, recalls Janssen back then as guarded, angry and not concerned with spiritual beliefs.

“He didn’t let folks in,” Beason said. “And he was not afraid at times to get pissed off in front of gatherings or to get pissed off at you.”

But Janssen kept hearing stories about the afterlife from patients — religious and non-religious alike — that chipped away at his beliefs.

One was from a young father dying of brain cancer.

The man was depressed. He wouldn’t get to see his children grow up. But his mood had improved when Janssen stopped by his hospital room one day. When Janssen asked why, the man had a surprising answer.

“He said, ‘Well, I had a visit from this little boy. He was about my kid’s age. He seemed happy. He told me, ‘Everything is going to be okay, and I’m here to help you.’”

The man told the kid that he wasn’t ready to go because one of his children had a birthday coming up. So the boy had agreed to return the following Tuesday.

The man’s depression lifted after that, Janssen said.

“And guess when he died?” he added. “The following Tuesday.”

Such stories might seem exaggerated, but science may explain them.

Many scientists say near-death visitations and other such episodes are caused by neurological malfunctions in dying people. It’s not uncommon for people close to death to experience “terminal lucidity,” a phenomenon in which they get sudden mental clarity, recognize loved ones and even speak to them.

Janssen said he was familiar with these explanations and believed them. But they couldn’t explain away all that he was seeing and hearing.

He cited the photos of the dying woman who had suffered from Alzheimer’s — the ones that caused him to wonder: What the hell is going on?

Janssen said Buddy, the woman’s husband, was not the type to exaggerate. Before he retired, he was a non-nonsense man who woke up at 3:30 each morning to deliver dairy products to stores.

Buddy had first noticed his future wife at a farm and garden store where she worked. For weeks he tried to work up the nerve to introduce himself but got tongue-tied. One day, she gave him a box of cookies she had baked for him.

“He told me, ‘She got tired of waiting for me to ask her out and figured the cookies would let me know she was interested,’” Janssen said.

Janssen didn’t see that version of May in her final months. The woman he met couldn’t raise her head in bed without assistance. Her neck muscles had lost strength. He only saw her with head slumped, her mouth ajar. She was almost completely nonresponsive.

But the photos Buddy showed him revealed another May. Buddy said he entered their bedroom when he heard a commotion. When he saw what was happening, he grabbed his camera and started taking pictures. The resulting images showed May sitting upright in her bed, gesturing with her hands to what appeared to be some unseen person.

Buddy said she also looked at him and thanked him for taking such good care of her while she was ill. She then turned to some unseen person and said, “It’s beautiful.”

Buddy told him that about an hour after he took the photographs, May died.

Janssen said what he saw wasn’t terminal lucidity.

“She was smiling — her eyes were almost like an illuminated blue,” Janssen recalled. “I was in uncharted territory. The woman’s brain had been progressively eroded with advance dementia. The neural networks had been destabilized. How could she know what Buddy had been doing? How could she even recognize him?”

Janssen said there’s a difference between deathbed visitations and drug- induced hallucinations, which are more fragmented.

“These (deathbed visitations) tend to be thematically consistent,” he said. “There’s a beginning, a middle and an end to the experience. Somebody arrives and lets them know, ‘I’m going to be here with you when you depart.’”

What clinched Janssen’s conversion, though, was not something he remembered. It was something he tried to forget.

It took place after midnight, as the snow was falling outside Janssen’s apartment in upstate New York. He was 23 at the time, a weary graduate student in Syracuse University’s history department.

Janssen said he was in bed when he was jolted awake by the sound of an ambulance siren.

Janssen hadn’t thought about that night for years. But one of his patients — the WWII veteran who saw the spectral presence beside his cot — triggered the flashback when he asked him, “You ever have something strange happen?”

Janssen had never told anyone what happened to him that night. It just didn’t fit into his worldview at the time, so he forgot about it.

Now he was being forced to remember.

After he woke, he was startled to pinpoint the source of the sirens. It was coming from the corner of his room. He heard a gurney being rolled on asphalt and a man say, “bring it here quick.”

Janssen went to the window but didn’t see anyone outside. He checked his pupils in the mirror and did math equations to ensure he wasn’t having a breakdown. Everything checked out.

He returned to sleep, thinking it was a vivid dream.

He was awakened again in the morning by a phone call. It was his father, telling him that his Uncle Eddie had been killed in a car accident. A startled Janssen asked when the accident occurred. His father told him – it was the exact time he was awakened by the siren, Janssen said.

Later that day, he received another sign. A malfunctioning radio on his table suddenly came on and began playing “Let It Be,” the song by the Beatles, which was inspired by a dream Paul McCartney had about losing his late mother. As he listened, Janssen said he was filled with an otherworldly sense of peace and comfort. The Beatles were one of his uncle’s favorite groups.

So after three decades of caring for the dying, what does Janssen believe now? His answer has evolved.

“Whenever people ask if I believe in God, I say yes. But the word God means so many different things to people,” he said. “I believe there is a unifying, conscious energy or force that connects us all. I think we go back to our source, which for me is God.”

He said he once saw death as an “invasive predator” that would annihilate him. But his patients taught him that human consciousness survives bodily death.

He also believes in something else now — people. He said his job has led him to reevaluate his opinion of the human species.

“It’s easy to go into these homes and see everything has broken,” he said about his visits to the dying. “But I’ve come to trust that beneath this surface, beneath the fear, we have this inner place of goodness, resilience and the ability to deal with and navigate things we didn’t think we could. For 33 years I’ve been watching people do it.”

Those who have known Janssen for years have noticed a change in him.

He’s much less judgmental,” said Patricia Hoffman, his sister. She said her brother values life so much now that he will remove a bug from his house or a poisonous snake from his yard instead of killing it.

“He sees the good in everyone. He has the ability to overlook all the rough edges and just get to the heart of who we are.”

Some of that change is due to his wife, Sarah. Janssen credits her for opening his mind to spirituality.

“He’s had these powerful experiences working with the dying that he couldn’t explain in his old way of looking at things,” Sarah Janssen said. “It’s forced him to open up in some way to a more unseen realm.”

Those experiences have also forced Janssen to open up to people in new ways. There’s a story that helps illustrate that change. It’s about another house call Janssen made to a grieving widower, about three years after he saw the photos of the woman with Alzheimer’s.

A nurse called him after midnight. She told him that Reba, one of his patients, had died. Her husband, Cliff, was having a rough time.

Janssen drove in the middle of the night to the couple’s house and found Cliff standing next to the body of his wife in her bed. Two beefy men in dark suits were about to take the body to a funeral home when Janssen noticed Cliff wince.

He asked Cliff if he wanted some final moments alone with his wife.

“Can we have a prayer first?” Cliff responded.

The assembled group — Cliff, two of his sons, Janssen and the men from the funeral home — gathered in a circle around Reba’s bed. They clasped hand and bowed heads. No one said anything.

Cliff squeezed Janssen’s hand and asked him to lead the group in a prayer.

Janssen swallowed hard. Earlier in his career in hospice, as a young atheist who thought only fearful people needed a god, he would have declined. He would have changed the subject.

But he saw the pain on Cliff’s face.

Janssen closed his eyes and winged it.

“Dear God,” he heard himself say. “We thank you for the life of Reba, and the lives she touched…”

When he finished, he thought he had botched the prayer. He had stammered too much. He opened his eyes and saw Cliff moving toward him.

Cliff gave Janssen a bear hug. He also honored him in a way Janssen had never experienced before.

He was weeping as he spoke.

“Thank you,” he said, “Brother Scott.”

John Blake is a CNN senior writer and author of the award-winning memoir, “More Than I Imagined: What a Black Man Discovered About the White Mother He Never Knew.”