CNN

—

Lesser known than some other beloved tales of larger-than-life heroes such as Gilgamesh, Beowulf and King Arthur, the Song of Wade is a case study in what happens when stories aren’t written down.

The epic was once widely known throughout medieval and Renaissance England — so popular that it was mentioned twice by Chaucer — but today it is mostly forgotten. Only a few phrases survive, and new research is showing how, when so little of a story is preserved, changes in a word or two can alter the entire tale.

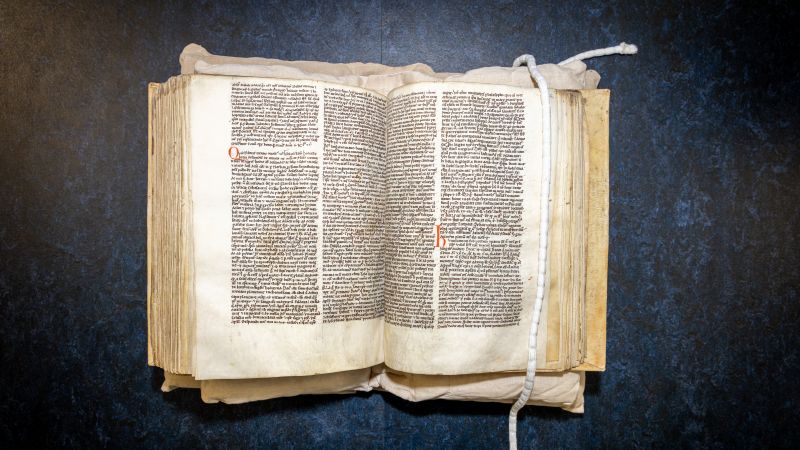

The Song of Wade originated in the 12th century, and its hero battled monsters — or so scholars once thought. The only known text was found nearly 130 years ago in a 13th- century Latin sermon, which quoted a bit of the saga in Middle English. In the excerpt, the word “ylues” was originally translated as “elves,” suggesting that Wade’s long-lost saga was teeming with supernatural creatures.

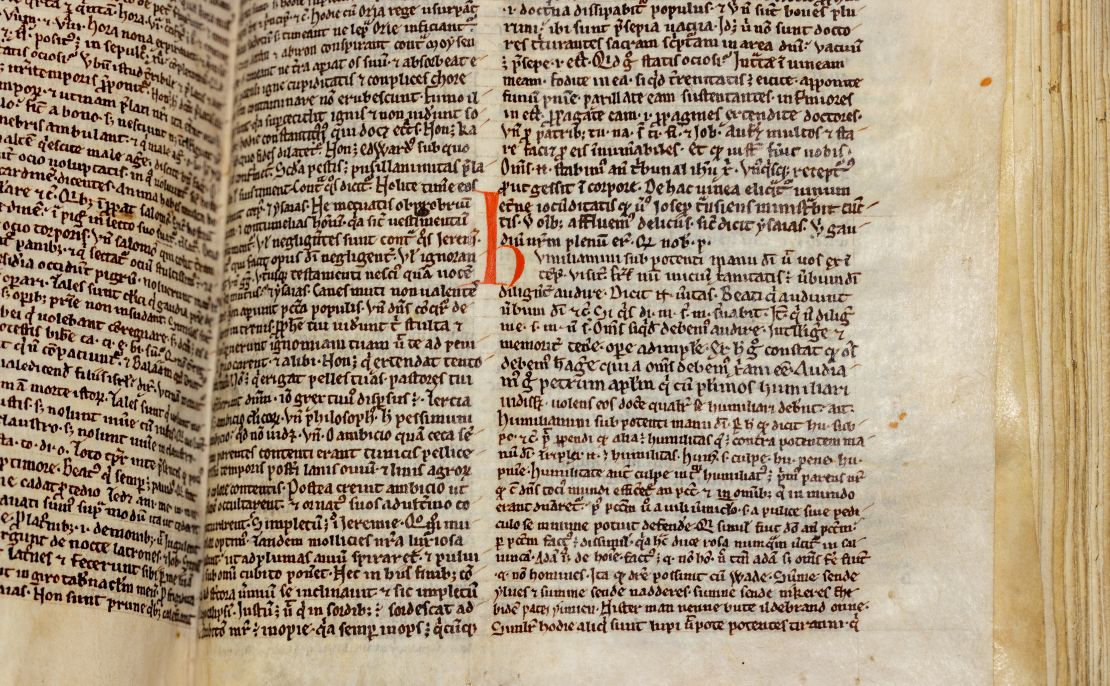

Researchers at the University of Cambridge in the UK have challenged that interpretation. They proposed that the word’s meaning was mangled by a scribe’s transcription error, which changed a “w” to a “y.” “Elves” is actually “wolves,” and the term was allegorical, referring to dangerous men, according to the analysis. Another word in the excerpt, translated as “sprites,” should instead be “sea snakes,” moving the story even farther away from the realm of the supernatural, the researchers reported July 15 in The Review of English Studies.

This new reading revises not only the phrases quoted in the sermon, but also the entire Song of Wade, centering the hero amid worldly dangers rather than mythical beasts. It overturns the picture of Wade as a literary twin to Beowulf, legendary slayer of the warrior-eating monster Grendel, said study coauthor Dr. Seb Falk, a researcher of science history and a fellow at Cambridge’s Girton College.

“He was more like a hero of chivalric romance (a literary genre celebrating knights, codes of honor and romantic love) like Sir Launcelot or Sir Gawain,” Falk told CNN in an email.

For hundreds of years, historians and literary experts have argued over why Chaucer would have mentioned the Song of Wade in his chivalric works. Recasting Wade as a courtly hero rather than a monster slayer makes Wade’s appearance in Chaucer’s writing a better fit and could help to uncover previously hidden meanings in those literary references, the authors wrote.

The new study is the first to analyze the Song of Wade excerpt alongside the entirety of the Latin sermon that quotes it, said study coauthor Dr. James Wade, an associate professor of English Literature at Girton College. (The surname “Wade” was relatively common in medieval England, and while Wade the researcher could not confirm a family connection to the storied hero, a link “isn’t impossible,” he told CNN in an email.)

In fact, it was the context of the sermon that led the researchers to the discovery that the fragment in English had been misinterpreted, Wade said.

The sermon was about humility, and it warned that some people “are wolves, such as powerful tyrants” who take “by any means.” There are other allusions to unfavorable animal traits in humans. As originally translated, the Song of Wade excerpt read: “Some are elves and some are adders; some are sprites that dwell by waters: there is no man, but Hildebrand (Wade’s father) only.”

For centuries, scholars have struggled to make sense of why references to “elves” and “sprites” were included in a sermon about humility. According to the new translation, the excerpt reads: “Some are wolves and some are adders; some are sea-snakes that dwell by the water. There is no man at all but Hildebrand.” Reinterpreted this way, the quoted phrases align more closely with the overall message of the sermon and redefine the genre of the story.

“We realised that taking the fragment together with its context would allow us not only to completely reinterpret the Wade legend, but also to reshape our understanding of how stories were told and retold in different cultural contexts, including religious contexts,” Wade said.

The long-standing difficulties in interpreting the excerpt are a reminder that paleography — the study of handwritten documents — “is not always an exact or precise science,” said Dr. Stephanie Trigg, Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor of English Literature at the University of Melbourne in Australia, “especially in the transmission of English and other vernacular texts without the standardised spelling and abbreviations of Latin.”

Focusing on the sermon is also important because this type of allusion to a popular epic was highly unusual, Trigg, who was not involved in the research, told CNN in an email.

“The authors are right to draw attention to the way the sermon seems to be quoting medieval popular culture: this is not all that common,” Trigg said. “It helps disturb some traditional views about medieval piety.”

When the preacher used the Song of Wade in his sermon, it was clear that he expected his audience to accept the reference “as a recognisable element of popular culture: a meme,” Falk said. “By studying this sermon in depth we get a wonderful insight into the resonances that such popular literature had across culture.”

Romantic and Fantastic

This new perspective on Wade’s saga doesn’t mean that it was based exclusively in realism. While there are no other known excerpts of the Song of Wade, references to Wade in texts spanning centuries offer details fantastic enough to delight fans of J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic “Lord of the Rings.”

“In one romance text, it’s said that (Wade) slays a dragon,” Falk said. “There is local folklore in Yorkshire, recorded by John Leland in the 1530s, that he was of gigantic stature.” Other texts stated that Wade’s father was a giant and that his mother was a mermaid, he added.

In fact, chivalric romance from this period frequently incorporated elements of fantasy, Trigg said. In the chivalric literary tradition, “romances often draw on mythological creatures and the supernatural,” and the distinction between chivalric romances and mythology “is not always rigorously made in medieval literature,” she added.

Still, aligning the Song of Wade more closely with medieval romances clears up long-standing confusion over allusions to Wade by Geoffrey Chaucer, during scenes of courtly intrigue in “Merchant’s Tale” and “Troilus and Criseyde.”

“Chaucer referring to a Beowulf-like ‘dark-age’ warrior in these moments is weird and confusing,” Falk said. “The idea that Chaucer is referring to a hero of medieval romance makes a lot more sense.”

While the Song of Wade has faded into obscurity, its appearance in the medieval sermon and in Chaucer’s work hints that for centuries the legend was a staple of popular culture in medieval England, even though there was no definitive text preserving the entire tale.

As its popularity waned, much of it vanished for good.

“By the eighteenth century there were no known surviving texts and nobody seemed to know the story,” Wade said. “Part of the enduring allure is the idea of something that was once part of common knowledge suddenly becoming ‘lost.’”

Mindy Weisberger is a science writer and media producer whose work has appeared in Live Science, Scientific American and How It Works magazine. She is the author of “Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control” (Hopkins Press).